Why we need a longer view of London’s high streets

To understand our high streets, we need to analyse their evolution across centuries, not decades

Reports of the fabled ‘death of the high street’ are premature. This unusually protracted demise is typically accompanied by references to the bustling high street heyday of the 1950s or even earlier. Blame is laid at the door of online shopping and out-of-town retail parks. Case closed.

The work of Laura Vaughan, Professor of Urban Form and Society at UCL's Bartlett School of Architecture, reveals the flaws in popular assumptions like these.

Retail had never been the majority activity in those places – not now, or in 1956, or even in 1875. One of Laura’s previous studies, the Adaptable Suburbs project, combined data on 20 small suburban high streets with other findings to demonstrate that retail is only one element of the diverse mix of activities needed to keep high streets and town centres in good health.

“Local activities like community services, offices, manufacturing and ‘third space’ recreational activities in cafes, pubs and clubs, all collectively contribute to the vitality and resilience of town centres,” says Laura. She adds that many of these contribute to people’s health and wellbeing.

“If these different purposes are situated on a route that connects not just people on foot, but from further afield too, then new social connections can be formed.”

The concept of interlinked networks turns up regularly in Laura’s work. Successful locations for urban activity tend to be easily accessible for more than one network.

“Having overlapping networks of smaller and larger town centres helps, and that’s a key feature of London and its suburbs. It’s not just about diversity of land uses — it’s a diversity of people moving through and around an area which makes for a livelier place.”

The same stretch of road is local in one section, and connected to the wider network in another. Loughton’s Church Hill/High Road. Photo: Dr Sam Griffiths.

The same stretch of road is local in one section, and connected to the wider network in another. Loughton’s Church Hill/High Road. Photo: Dr Sam Griffiths.

Building on a Bartlett legacy

Trained initially as an architect, Laura is a Professor and the Director of the Space Syntax Lab at The Bartlett School of Architecture. Reflecting the broad scope of her investigations, she’s also a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Historical Society.

“People often mistake me for a planner, because the work I’m involved in is very relevant to planning, policy and public health.”

Her diverse outputs sit at the intersection of multiple disciplines. As well as a prodigious catalogue of journal articles, academic books and papers, Laura regularly publishes a fascinating blog full of entertaining details and reflections on the urban histories she explores.

Appropriately for a historian, much of her work as Director of the Space Syntax Lab builds on theories and approaches devised almost half a century ago at UCL. Pioneered by Professor Bill Hillier (on whose work Laura has recently co-edited a book), space syntax methodologies provided architecture with an entirely new scientific basis.

Through mathematical analysis, space syntax helps architects and planners understand how cities work. A key variable is the number of connections between the different locations within the network. The more directly accessible a place is, the more likely it is to be a central location that people travel through and use.

Stepping back to

see the stories of London's suburbs

Laura’s work shows how these highly connected locations are often established over centuries, with a greater continuity of land use than you might expect.

Suburbs like Chipping Barnet or Islington are urban centres in their own right that have long played a historically important role in relation to London. Barnet was established in the 12th century as a market town on the Great North Road that leads northward out of London, and its continuing success as a vibrant and prosperous suburb is partly due to these same factors.

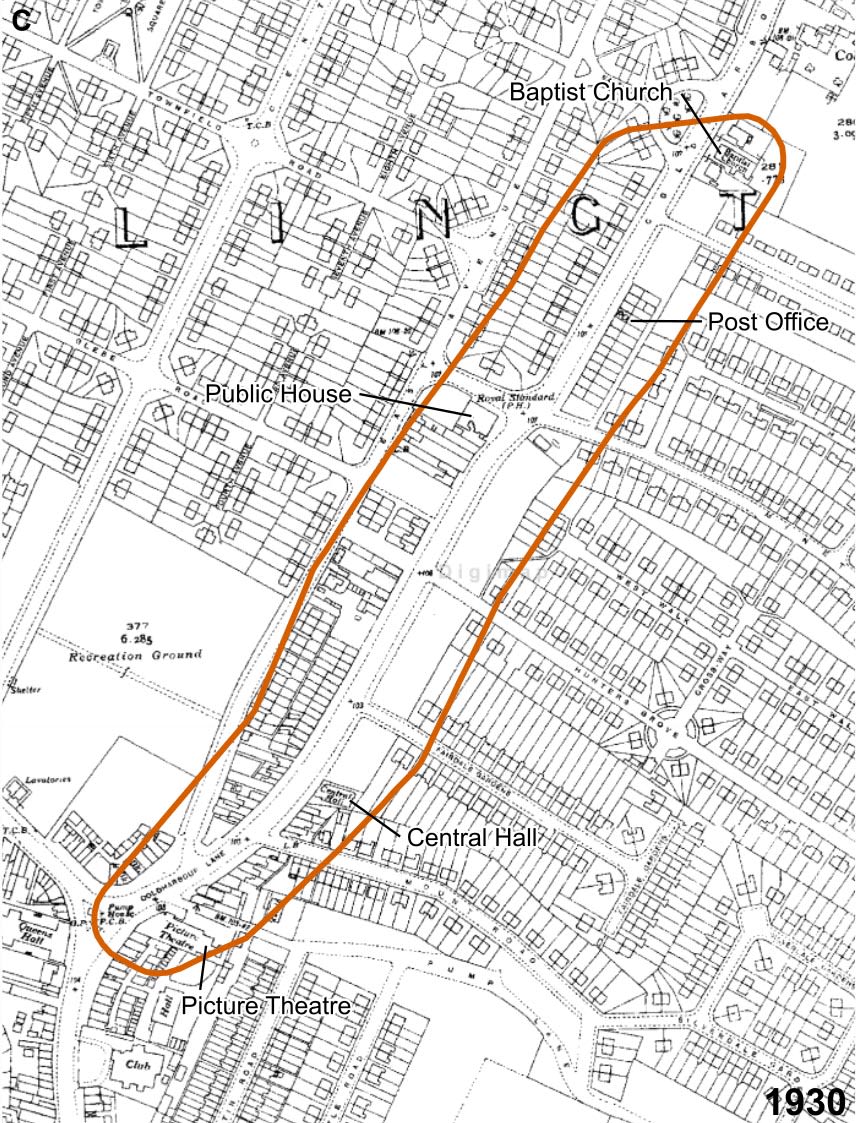

There are also lots more recent, equally compelling stories that space syntax can tell us. Mapping the connections between places lets us understand the changing history of the high street and allows us to identify the era in which a high street developed – almost like counting the rings on a tree trunk.

During four distinct epochs, ranged between roughly 1840 and the post-war period of the 1950s, we can trace the influence of major changes such as the coming of the railways or suburban housing estates and new towns.

With the last of these epochs characterised by high streets that are less likely to be connected to the wider networks, we start to see how urban planning strategies and decisions can profoundly impact the life of the city, and successive generations of people who live in it.

Victoria Road, Surbiton 1907/2017: montage of postcard from the private collection of Dr Ruth Davies, with a contemporary photograph of the street. Credit: Dr Garyfalia Palaiologou, Adaptable Suburbs.

Victoria Road, Surbiton 1907/2017: montage of postcard from the private collection of Dr Ruth Davies, with a contemporary photograph of the street. Credit: Dr Garyfalia Palaiologou, Adaptable Suburbs.

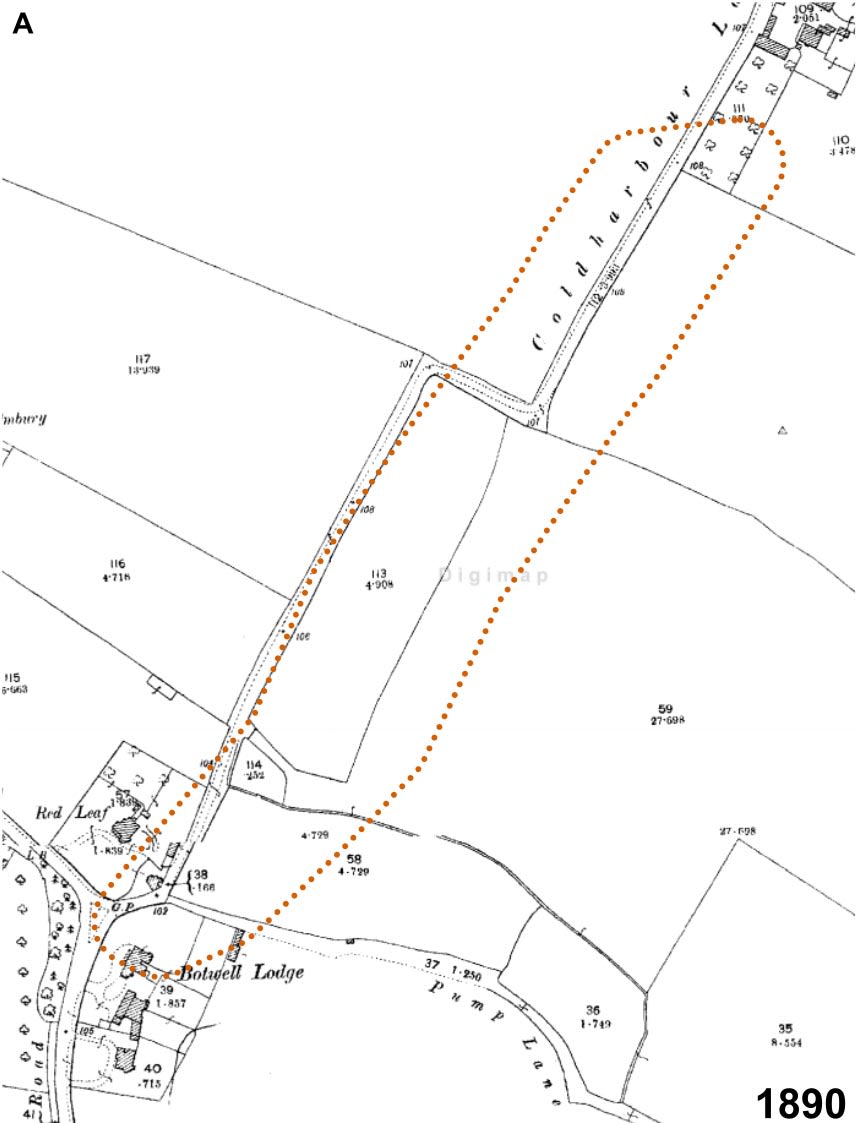

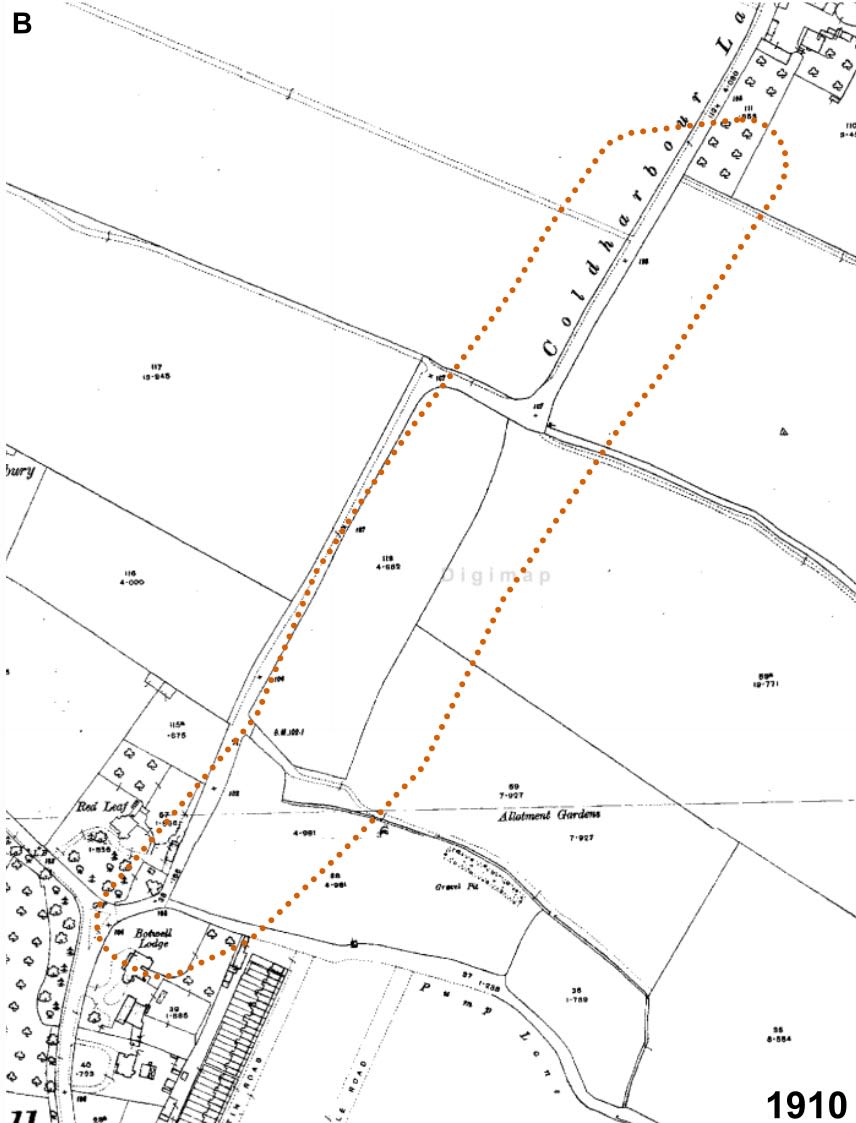

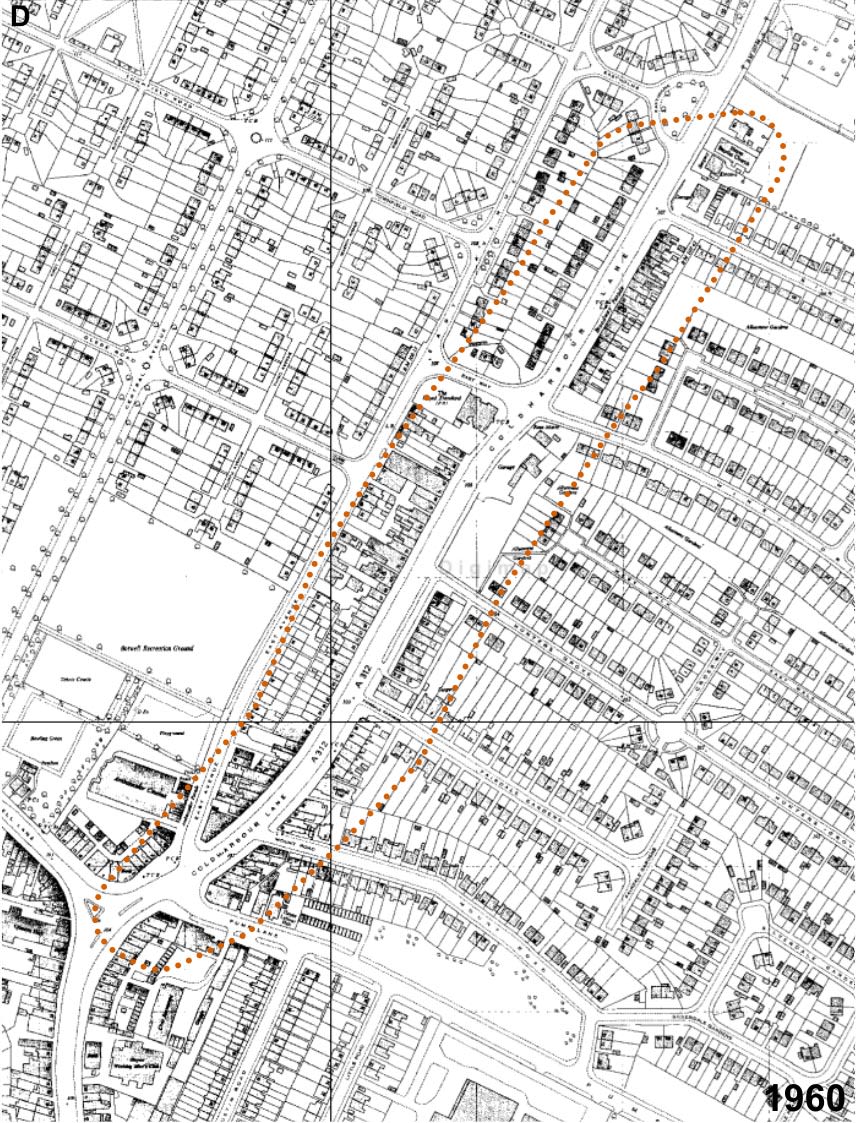

The evolution of Coldharbour Lane, Hayes, Greater London into a high street. Maps: Dr Kimon Krenz (contains data from © Ordnance Survey Limited 2024).

The evolution of Coldharbour Lane, Hayes, Greater London into a high street. Maps: Dr Kimon Krenz (contains data from © Ordnance Survey Limited 2024).

The evolution of Coldharbour Lane, Hayes, Greater London into a high street. Maps: Dr Kimon Krenz (contains data from © Ordnance Survey Limited 2024).

The evolution of Coldharbour Lane, Hayes, Greater London into a high street. Maps: Dr Kimon Krenz (contains data from © Ordnance Survey Limited 2024).

The evolution of Coldharbour Lane, Hayes, Greater London into a high street. Maps: Dr Kimon Krenz (contains data from © Ordnance Survey Limited 2024).

The evolution of Coldharbour Lane, Hayes, Greater London into a high street. Maps: Dr Kimon Krenz (contains data from © Ordnance Survey Limited 2024).

The evolution of Coldharbour Lane, Hayes, Greater London into a high street. Maps: Dr Kimon Krenz (contains data from © Ordnance Survey Limited 2024).

The evolution of Coldharbour Lane, Hayes, Greater London into a high street. Maps: Dr Kimon Krenz (contains data from © Ordnance Survey Limited 2024).

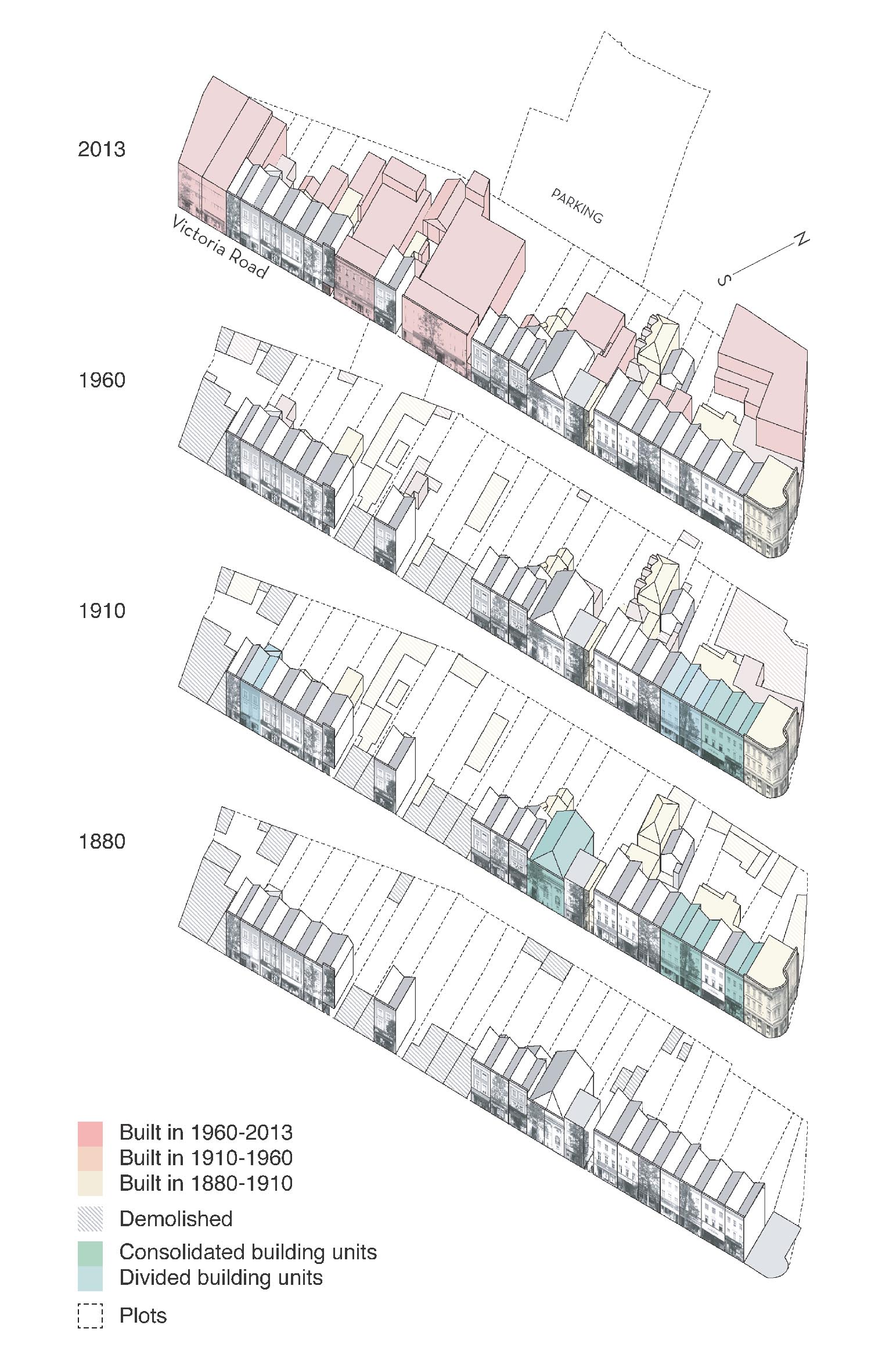

Continuity, adaptation and change: Axonometric projection of the built form changes over time on the north side of Victoria Road, Surbiton © Dr Ilkka Törmä

Continuity, adaptation and change: Axonometric projection of the built form changes over time on the north side of Victoria Road, Surbiton © Dr Ilkka Törmä

Supporting a flexible, resilient high street

Positive changes that invigorate our high streets and public spaces can often stem from small interventions, too.

Laura emphasises the importance of adaptability.

“It’s really, really hard to reorientate a street. It's one of the reasons they persist. Buildings are also quite rigid – but if they’re constructed sensibly, they can be adapted.

“19th century terraced houses, or even 20th century suburban houses, lend themselves well to adaptability. You’ll find dwellings converted to shops below, offices above, and then converted back again to family houses as things change.

“The relationship between streets remains the same, but land uses themselves can change really fast.

“A local authority with foresight, enabled by central government, can allow for a great deal of flexibility. It’s important to think very carefully when converting to residential, however.

“That’s an inherently different way of using that bit of the street. Suddenly, you’re closing off what would otherwise be an open, vital aspect of the public realm.”

“19th century terraced houses, or even 20th century suburban houses, lend themselves well to adaptability. You’ll find dwellings converted to shops below, offices above, and then converted back again to family houses as things change.”

Professor Laura Vaughan, The Bartlett School of Architecture

About the author

Professor Laura Vaughan

Professor of Urban Form and Society and Director of the Space Syntax Lab, Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL.

Laura Vaughan has extensive experience of research into the relationship between urban form and society using space syntax methods to consider some of the most critical aspects of cities and society, ranging from spatial inequalities and health, poverty and housing, to economic and social vitality.

The Bartlett in London: celebrating 200 years of UCL

This story is part of the Bartlett in London series from the UCL Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment.

In celebration of UCL's bicentenary in 2026, this series of stories explores our impact on the built environment of London – from creating healthier and more sustainable living, to supporting local communities and documenting London’s rich history.

Produced with support from the UCL Innovation and Enterprise Faculties Innovation Fund.

Explore architecture and urban design through the lens of people and space

UCL's Space Syntax MSc offers specialised knowledge to those interested in the research and design of the built environment, from architectural to urban scales. It is designed for individuals aiming to pursue an academic pathway or to deepen their expertise within their current professional practice.

Story produced by All Things Words

© UCL The Bartlett 2025

This story was produced with support from UCL Innovation and Enterprise Faculties Innovation Fund.