Uncovering the health inequalities in London housing

UCL researchers are investigating the vicious cycle of sickness caused by low-income London housing

Currently, the greatest environmental threat to health in the UK is long-term exposure to air pollution.

There are a whole host of associated health problems that include respiratory and cardiovascular complications, birth defects and asthma. There’s also growing evidence that pollution affects cognitive function, increasing the likelihood of depression, schizophrenia and dementia.

Pollution is far from the only environmental risk to our wellbeing. As the climate crisis intensifies, hotter weather and rising temperatures pose an increasing hazard to health, endangering lives through heat stroke and heat exhaustion.

What links these two threats is the fact that they can both be avoided – especially if you’ve got the money. Risk of death from preventable health conditions is three times higher for people living in the poorest areas of the country, compared with those in the least deprived areas.

Now, researchers from the UCL Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering (IEDE) are building a solid base of evidence to prove that one of the main factors that determines your level of risk is the building you live in.

Photo credits: Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering, UCL

Photo credits: Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering, UCL

Drawing on diverse data sources and systems thinking to see the big picture

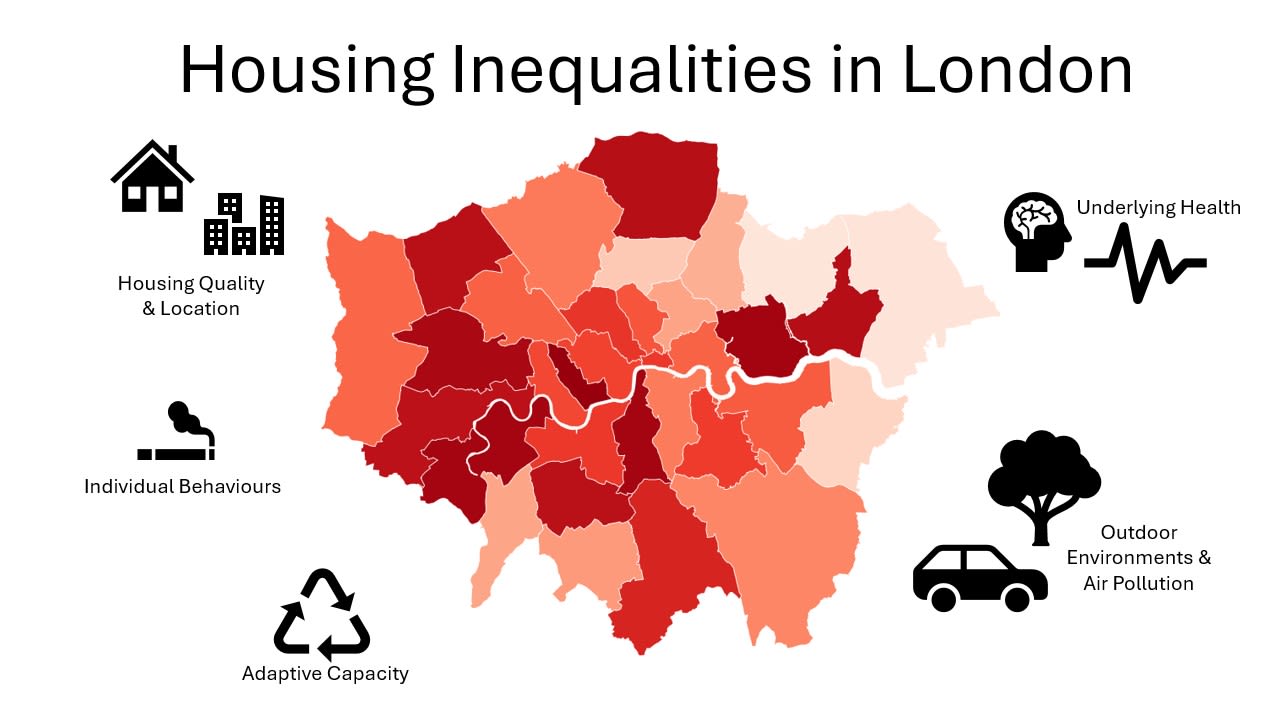

This crucial body of research focuses on the links between housing and health. With its diverse neighbourhoods and housing stock, the Greater London area provides an excellent case study for this research.

The IEDE researchers used a systems thinking approach to investigate the complex connections between housing, socio-economic status, health and the effects of both air pollution and heat risks.

Dr Phil Symonds, a lecturer on the UCL Environmental Design and Engineering MSc course, explains. “It’s linking together lots of different data sets, so we can tie together the exposures, the types of occupants who are being exposed, and also their ability to adapt.

“When you look at these things in connection with one another, you can identify reinforcing feedback loops, where increased exposures lead to health impacts, which in turn makes people more vulnerable to the exposure.”

Phil's colleague Lauren Ferguson, former research fellow at the IEDE, and now conducting postdoctoral research at Harvard School of Public Health, gives us a typical example of how a feedback loop might work in practice.

“If you live in poor housing with high levels of indoor air pollution or heat, this can make you sicker. Then you might end up having to take time off work, which can result in an income penalty.

“As a consequence of that, you’ll have fewer resources to combat the problem, whether that’s fixing a broken extractor fan, or installing air conditioning.”

The team drew on time use surveys to find out more about the lifestyles and health of different groups of occupants, analysing the responses to questions about time spent indoors and outdoors, cooking and other relevant factors.

Dr Giorgos Petrou, another of the IEDE team involved in the research, acknowledged the value of co-developing their research alongside non-academics.

“It wasn’t just UCL – we worked alongside people from different organisations, including UK public health agencies. That’s helped us bring the work outside the academic environment, and closer to policy makers.

“Taking a systems approach and engaging with different partners highlighted the value of including multiple voices during the design and implementation of our research. It’s provided a strong case for interacting with them from the very start of our projects.”

“The main synergy for indoor air pollution and heat is for housing with limited volume and an airtight envelope. That’s the worst of both worlds”

Dr Phil Symonds, UCL Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering (IEDE)

The ruinous results of overcrowding

Two of the groups' papers on air pollution have served to highlight the perhaps lesser-understood risks of indoor air pollution, to which lower-income Londoners are often disproportionately exposed.

Phil says, “Lauren’s paper highlighted the fact that lower-income groups are more likely to have faulty extractor fans, and often don’t have windows with trickle vents, so air pollution from cooking is a bigger problem.”

Lauren adds, “there’s also a significant difference in the health impacts of different cooking fuels. Gas stoves, which are the dominant cooking fuel across the whole population of London, lead to greater concentrations of PM2.5 in the home. A study from the US that indicated that more than 12% of childhood asthma could be attributed to domestic gas stove use.”

Similarly, two of the groups' papers on heat risk found that housing can play a crucial factor in occupant exposures to overheating. One of the papers used thermal simulations of 12 different randomly selected flats from around inner London. Due to factors like layout, ceiling height and types of window, the team found temperature differences of up to 3.5 °C in the bedrooms, and 2.2 °C in kitchens.

These inequalities due to differences in the space are also exacerbated by issues like noise pollution, which has a greater effect in lower-income housing and leaves people reluctant to open windows, even in hot weather.

The findings corroborated an earlier study by Giorgos that showed how vulnerable households (those on means-tested or disability benefits) experienced statistically higher summertime indoor temperatures.

Phil points out that some features of lower-income housing were exacerbating the health impacts of both indoor air pollution and heat risks.

“The main synergy for indoor air pollution and heat is for housing with limited volume and an airtight envelope. That’s the worst of both worlds – there are higher concentrations of indoor pollution, because there’s a lower volume of air for it to dilute into.

“And the limited space can lead to heat buildup, without anywhere for it to escape, especially when there are flats above, below and to the sides.”

Giorgos explains how the pressure on the housing market in London also increases the health inequalities.

“In terms of reduced floor space, converted houses can be even more problematic.

“You end up with spaces which were designed to be living rooms used as bedrooms, and overcrowded homes where the original design intent isn’t followed.”

Tackling the issues from all angles

The IEDE researchers are planning to expand the focus of their studies beyond housing, and examine how pollution, heat and cold risks interact with other sectors such as transport.

They’re also examining different ways to present their work for different audiences, increasing its value and impact for both decision makers and the public. Phil and Giorgos are working closely with the Climate Change Committee, Greater London Authority and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero.

Giorgos says, “We need both top-down and bottom-up approaches to effectively address these issues. Cost-benefit perspectives aren’t always the best way to think about exposures and health impacts, but they’re often very relevant to how money for public health is invested.”

Lauren concludes, “While we’re waiting for the policy to catch up, it’s worth remembering that small things can make a difference. Remembering to turn on your extractor fan while cooking, waiting until the traffic dies down before opening your windows in the morning – over time, these minor things could make a real difference to your health.”

About the authors

Dr Phil Symonds

Lecturer in Built Environment Analytics, Institute for Environmental Design & Engineering, UCL

Dr Giorgos Petrou

Senior Research Fellow in Building Physics Modelling, and Scientific Manager, Institute for Environmental Design & Engineering, UCL

Lauren Ferguson

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Environmental Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

The Bartlett in London: celebrating 200 years of UCL

This story is part of the Bartlett in London series from the UCL Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment.

In celebration of UCL's bicentenary in 2026, this series of stories explores our impact on the built environment of London – from creating healthier and more sustainable living, to supporting local communities and documenting London’s rich history.

Produced with support from the UCL Innovation and Enterprise Faculties Innovation Fund.

Learn more about health, wellbeing and sustainable buildings

Gain the skills and tools to lead on health and wellbeing in sustainable building design, retrofit and operation.

Story produced by All Things Words

© UCL The Bartlett 2025