Tackling household air pollution

We’re only just beginning to understand the health impacts of household air pollution. In this article, three leading experts discuss what happens when 2.4 billion people still can’t access clean fuels for cooking.

In 2023, the annual Lancet Countdown report (which focuses research efforts on climate change and human health) included household air pollution for the first time as one of its indicators.

Including household air pollution as a distinct indicator in the Lancet Countdown report not only highlights the significance of this research but also helps policymakers identify opportunities to drive positive change in this underexplored area.

Tackling this global problem won’t be easy. In the 62 countries analysed in 2020, roughly one third of the population were forced to rely on dirty fuels (coal, charcoal, wood or other biomass) as their primary energy source for cooking.

Using these fuels indoors exposes you to toxic concentrations of polluting particulate matter, resulting in roughly 140 deaths for every 100,000 people, and additional health complications for many more.

To make matters worse, surging energy prices and their knock-on economic effects may force an additional 100 million people to resort to dirty fuels.

“There’s a global problem,” says Dr James Milner, associate professor at the Department of Public Health, Environments and Society in the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

“The absolute numbers are going up. So this is a problem that isn’t going away anytime soon.”

Another co-author of the Lancet Countdown report, Dr Shih-Che Hsu, a research fellow in Building Stock and Indoor Air Quality Modelling at UCL Energy Institute, agrees.

“The particles don’t just get into our lungs. They’re increasingly being detected in other parts of our bodies. They’re being detected in brain tissue, and they’re crossing the placenta in pregnant women.”

“The particles don’t just get into our lungs. They’re increasingly being detected in other parts of our bodies. They’re being detected in brain tissue, and they’re crossing the placenta in pregnant women.”

Dr Shih-Che Hsu, UCL Energy Institute

Global patterns of pollution

Much of James’s research involves the mathematical modelling of the health effects of climate change mitigation actions. In his work on the report, he found correlations between overall air pollution concentrations, household air pollution and the level of economic development.

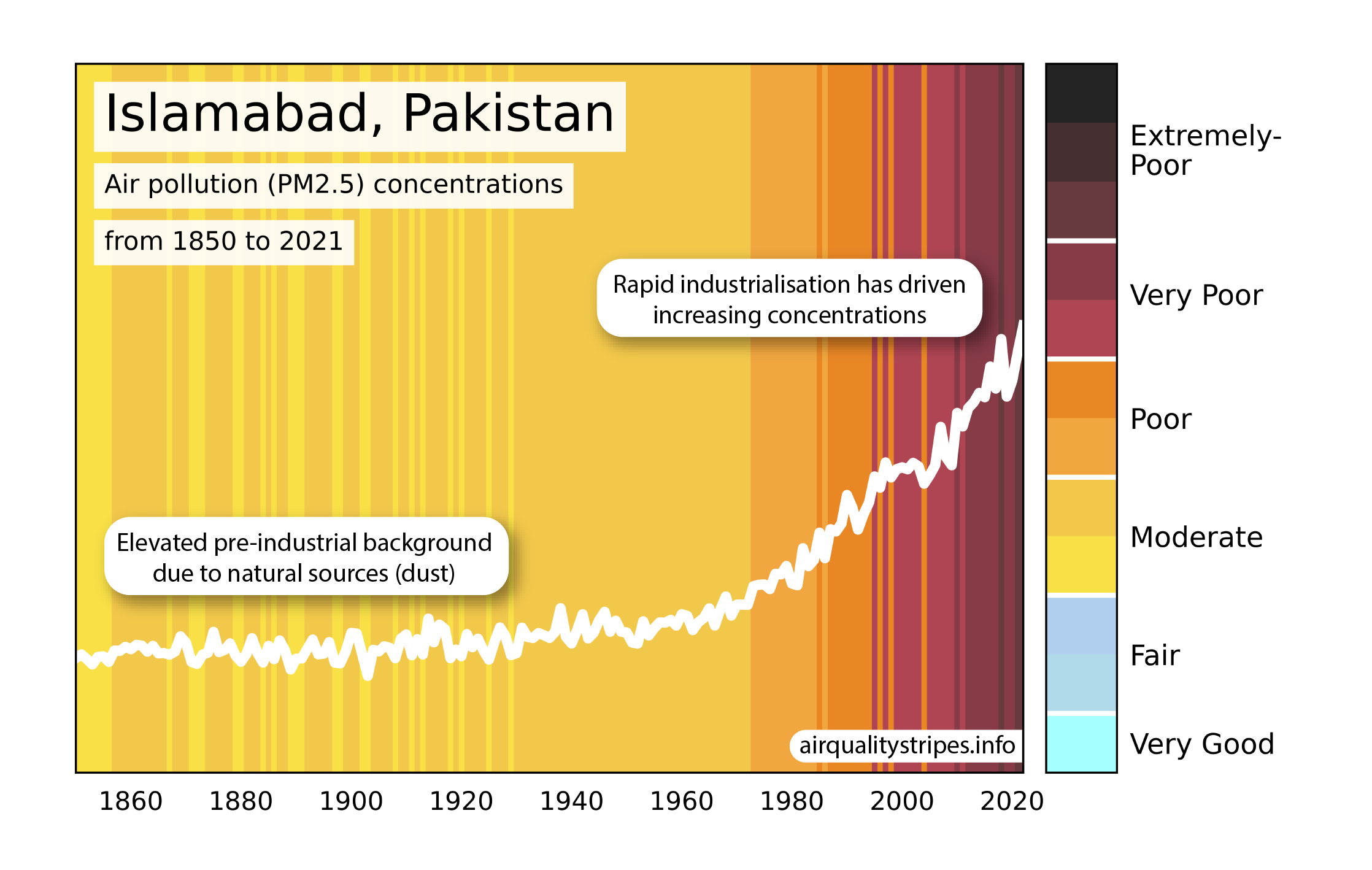

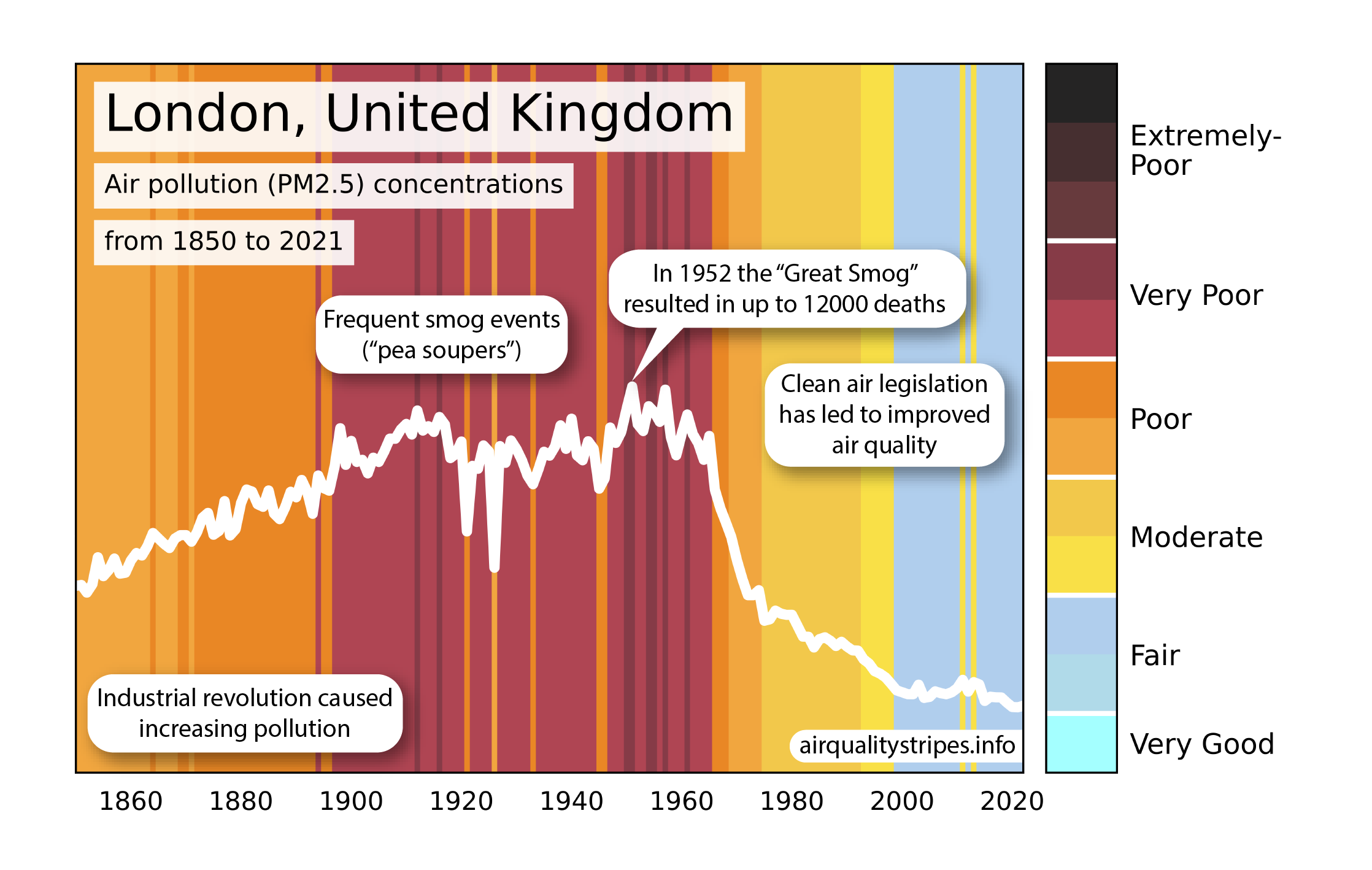

“In general, what you see is higher air pollution concentrations closer to the equator, particularly in places like South and East Asia, North Africa, the Middle East.

"There are lots of reasons why the level's different in different parts of the world, but it's mostly about economic development and the nature of the sources - that might be industrial traffic, farming, household energy and all sorts of things.

“So gradually, wealthier countries have tended to shift to cleaner technologies and that's starting to happen in other parts of the world.

“A good example is China, where they declared war on pollution about 10 years ago. Since then, they've managed to reduce pollution concentrations in some places by 40 to 50%. That's been estimated to increase people's life expectancy by about two years in those areas.”

Behind closed doors – the challenges of household air pollution research

"Household air pollution requires much more specific, localised study which can be resource-intensive and difficult to conduct comprehensively,” says Dr Nahid Mohajeri – programme lead for Sustainable Built Environments, Energy and Resources at UCL Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering (IEDE).

“As a result, I would say there’s been a lot less research in this area available in comparison to outdoor air pollution.”

Nahid’s valuable contribution to the Lancet Countdown report also included the publication of a methodology report in the Lancet Planetary Health journal, which showed how the team working on the household air pollution indicator were able to draw on a much wider and more sophisticated range of data sources than ever before.

“We brought a lot of new data, which helped us make it much more accurate, compared with previous similar research.

“We were able to take into account some of the climate change metrics - things like ambient air pollution and heating degree days (a measurement designed to quantify the demand for energy needed to heat a building). These metrics hadn’t been included in previous estimations.

“Most of the research bodies have historically focused primarily on outdoor air pollution - mainly because it is easier to monitor (and therefore regulate) than indoor air pollution.

“However, with increasing availability of data and also new methodologies using artificial intelligence, there’s lots of new solutions to help us collect and combine data. Hopefully, we can now bring some new ways of quantifying and dealing with indoor air pollution.”

“I don't think people think very much about indoor sources of air pollution. I don't think it's just the media - I think a lot of people, for one reason or another, don't appreciate the dangers of the exposure they might face indoors.

Dr James Milner, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Raising the alarm on a global crisis

Unfortunately, this comparative lack of research focus has made it much harder to raise public awareness.

James says, “I’d say we probably haven’t managed to get enough attention, although it’s definitely grown a lot over the last decade or so.

“I don't think people think very much about indoor sources of air pollution. I don't think it's just the media - I think a lot of people, for one reason or another, don't appreciate the dangers of the exposure they might face indoors.

“A few years ago we did a study on attention given to air pollution for people living in informal settlements in Nairobi. Air pollution wasn't the main priority for those people, given that they might have greater concerns for access to food and water and energy.

“It’s perhaps not always unexpected that air pollution might not be people's highest priority.”

Refining the indicator for greater research impact

All three academics are very pleased that the household air pollution indicator is now included in the annual Lancet Countdown report. However, there’s still many avenues to investigate for future study.

Shih-Che says, “I think establishing the household air pollution indicator is just the start.

“We need to find a way to investigate personal exposure. Not everyone spends the same amount of time in the home. I think the take-home message for me is that the difference between indoor exposure and personal exposure is a very important one.”

“There’s also big differences between the country and the city – and even between the urban and rural areas in the countryside.”

Nahid agrees that the differences between household air pollution in urban and rural settings warrants further investigation.

“The rural households suffer much more from air pollution. This is what we found out. The inequalities are primarily related to the socioeconomic aspects of the households, and the cooking equipment used.

“We could potentially mitigate some of this inequality by increasing access to clean energies and better technologies.”

From a health perspective, the academics are also hoping to shed more light on the disproportionate impact of household air pollution on women and girls.

Across the 62 countries in the sample, women and girls faced a much larger proportion of the time consuming tasks associated with household energy, such as cooking indoors or searching for biomass to burn.

This both increases their exposure to indoor particulate matter and reduces their opportunities for education or economic independence through paid work.

As James says, “there’ll certainly be ways we can improve this indicator. We can expand it to more countries, and we can focus more closely on inequality – how different people are exposed in different ways.

“Household air pollution is something that’s largely preventable. Although not all air pollution is from human sources, this is something we can take action on...something we can actually do something about.”

About the authors

Dr James Milner

Associate Professor in Climate Change, Enviornment and Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

Photo by Appolinary Kalashnikova on Unsplash

Photo by Appolinary Kalashnikova on Unsplash

Learn more about our sustainable building design and engineering master's degrees

Our master's degrees explore all aspects of sustainable building design, engineering and operation preparing you for a career building a more healthy, more sustainable built environment.

Photo by Appolinary Kalashnikova on Unsplash

Photo by Appolinary Kalashnikova on Unsplash

Learn more about Economics and Policy of Energy and the Environment

Our industry-leading master's degree in Economics and Policy of Energy and the Environment trains you in the economics, policy, and modelling skills that you need to be part of the global solution.

Story produced by All Things Words

© UCL The Bartlett 2024