Sharing the untold stories of London

A unique UCL research project is telling the story of the people and events that have shaped our city and UCL’s Bloomsbury campus

Sir John Summerson by Walter Bird, 1966. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Licensed under CC by 3.0

Sir John Summerson by Walter Bird, 1966. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Licensed under CC by 3.0

For 131 years the Survey of London has unearthed the hidden stories of our capital’s buildings. Now they’re telling a story of explosive growth – the story of UCL.

“The Survey will never be finished. If the time comes when a final “coverage” seems to be in sight, it will be time to begin again.”

In John Summerson’s heyday during the 1930s and 1940s, the Survey was a means to protect endangered buildings. Since 1894, a motley collection of architects, amateurs and enthusiasts (supported by the London County Council) had been diligently cataloguing the capital’s most important built landmarks.

Interweaving their painstaking maps and drawings with social and cultural insights, the Survey was used to strengthen the case for preserving these valuable buildings and places, as well as providing an ‘emergency list’ of those under imminent threat.

After the Town and Country Planning Acts of 1944 and 1947, when buildings of historical interest became listed and protected, the purpose and scope of the Survey changed.

Colin Thom, who, as Director of the Survey of London at UCL’s Bartlett School of Architecture, has devoted more than 30 years to this remarkable endeavour, explains how these changes led to the development of a research project unlike anything else in the world.

“Once listing came in, and that emergency recording aspect of the Survey’s work was no longer needed, it could quite easily have stopped altogether.

“Instead, they changed tack, and the Survey became a professional work of urban history. Now it was the story of all the buildings. Not just the ones deemed worthy of listing, but people’s terraced houses, their corner pubs, their schools. They documented the processes that brought these buildings into being, and the kind of people and industries that moved into and out of the area.

“It became more about explaining London to Londoners, and telling the story of how the city has developed in the way it has.”

“The value of what we do is being able to encapsulate some of these big stories in a much shorter, more readable way, that puts the story back in the context of the local area.”

Colin Thom, Director of the Survey of London

The Survey in the age of technology

The Survey’s captivating combination of social storytelling, beautifully drawn artwork and meticulous architectural research is accessible to the public in its entire physical form. Exploring these large blue volumes — part-reference book, part-artefact — readers will discover forgotten histories and fresh perspectives on both famous and not-so famous people who’ve shaped the city.

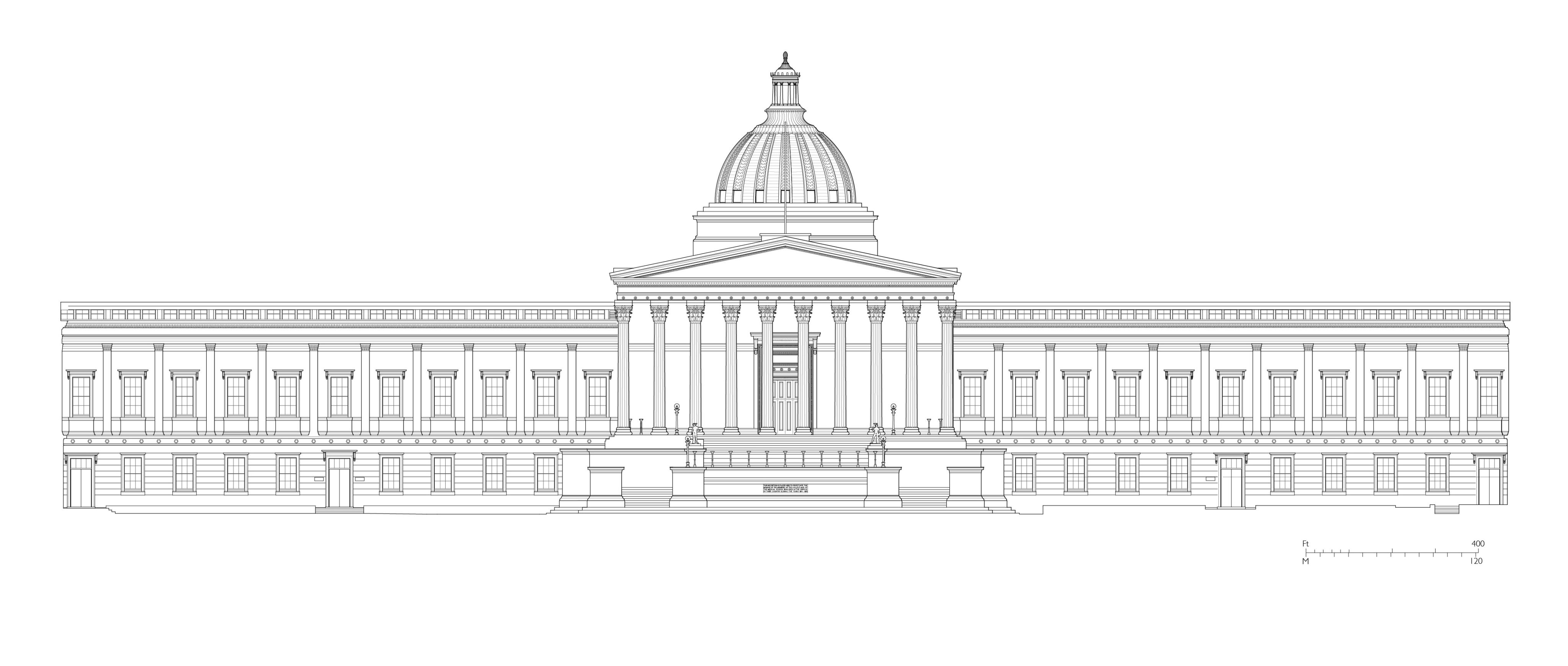

West front of the Wilkins Building in 2024. © Drawing by Helen Jones for the Survey of London, based on fieldwork and drawings kindly supplied by UCL Space Team

West front of the Wilkins Building in 2024. © Drawing by Helen Jones for the Survey of London, based on fieldwork and drawings kindly supplied by UCL Space Team

Built environment methodologies and architectural research allow the Survey’s creators to provide a uniquely balanced retelling of many significant historical events.

In recent years, the Survey team has found new ways to share its work with wider audiences – most notably through a collaborative research project with The Bartlett Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis at UCL, which brought together public contributions with research by Survey historians.

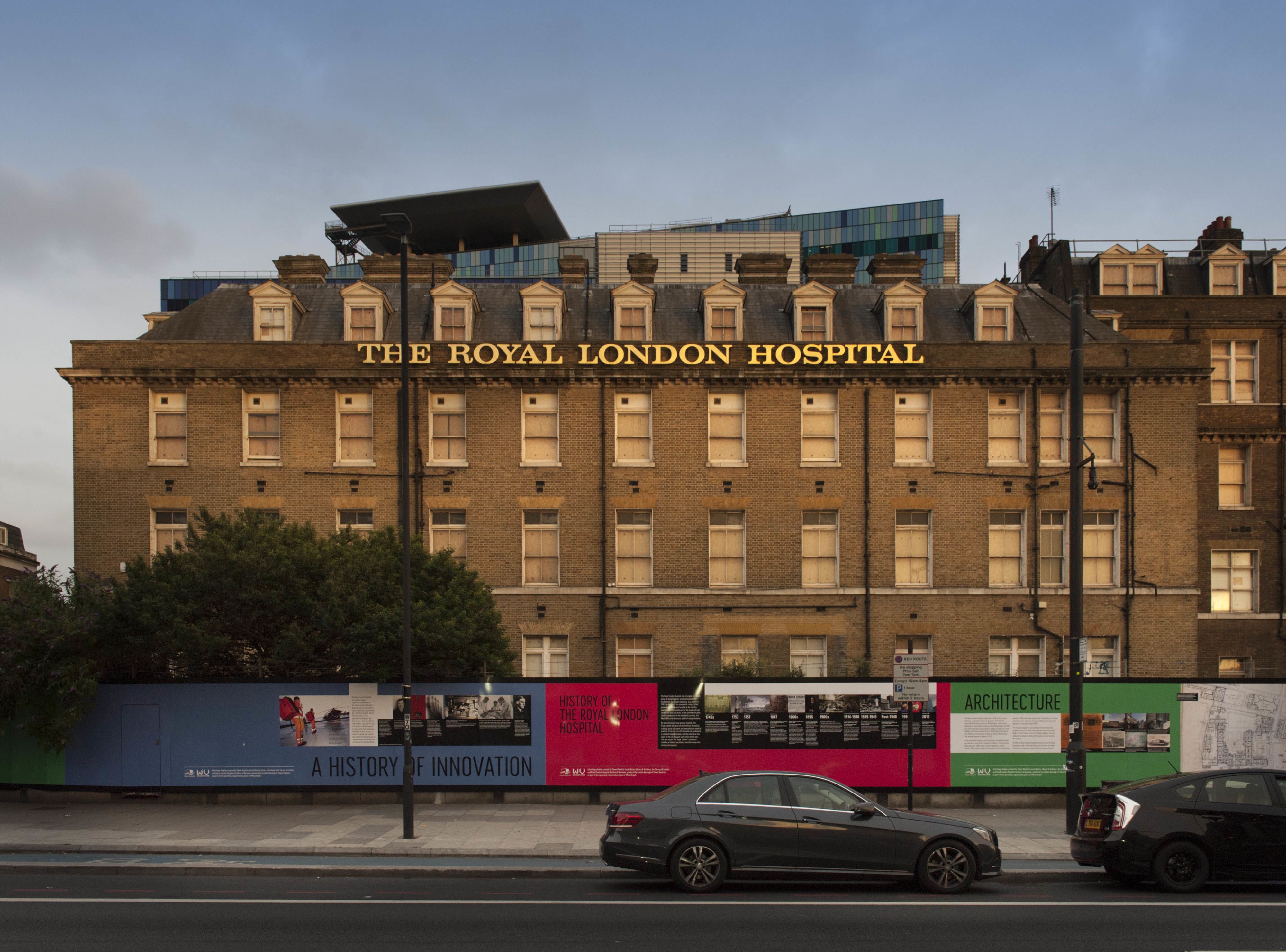

Focused on Whitechapel, this project supplemented the Survey’s usual research methods of documentary research and field investigation with oral history interviews and public engagement. People in the area were asked to contribute their photos and memories, resulting in a rich body of data that was then shaped into a variety of different outputs.

The Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel Road, view from the north in 2017, showing hoardings created in a collaboration between the Survey of London, Tower Hamlets Council, Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives, and the Royal London Hospital Archives at Barts Health NHS Trust. © Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel Road, view from the north in 2017, showing hoardings created in a collaboration between the Survey of London, Tower Hamlets Council, Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives, and the Royal London Hospital Archives at Barts Health NHS Trust. © Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Along with workshops, walking tours and two Survey volumes, the project created an immersive website that allowed users to explore the histories of Whitechapel.

“I’m glad to say the latest book we’re working on — the UCL monograph — has an online version that’s designed specifically for that readability,” explains Colin.

The untold story of UCL’s urban impact

UCL’s own Bloomsbury site has been covered before in the Survey — back in 1949, as part of Volume 21 which explored Tottenham Court Road and the parish of St Pancras.

There are still areas of London (particularly south of the Thames) which haven’t yet been examined — so why are the Survey’s historians choosing to reinvestigate Bloomsbury?

One of the main reasons for the new monograph is the radical changes to the area brought about by UCL itself. From the brief glimpse offered in Volume 21 of a bombed-out Wilkins Building and Main Quadrangle on Gower Street, UCL’s campus has rapidly expanded to encompass a significant part of London’s Bloomsbury district, fundamentally changing the character of the area.

Next year marks the 200th anniversary of UCL’s foundation, and our bicentenary provided further impetus for the creation of a Bloomsbury monograph — an undertaking that was begun by Dr Amy Spencer, who joined the Survey team at The Bartlett School of Architecture in 2015.

Amy is understandably excited about the opportunity to share the architectural history of UCL — an account that some feel is long overdue.

“While the architectural histories of other universities like Edinburgh and Glasgow have been the subject of recent monographs, this aspect of UCL’s history has been neglected. In this first complete account, we’ll be tracing the adaptation and construction of buildings in parallel with changes in education, society and technology.

“We’ll also be addressing some significant gaps in knowledge, and clearing up some misapprehensions, too.”

Much of what’s been written about UCL’s architecture so far has been heavily focused on the way the neoclassical design of the Wilkins Building and Main Quadrangle reflects the secular principles on which UCL was founded. Amy explains why.

“Before UCL was established, if you wanted a degree you had to subscribe to the tenets of the Anglican Church. In contrast, UCL was founded as a university that would be open to people of any creed or faith.

“So, there’s always been a lot of interest in connecting these founding values to the neoclassical style, which is associated with ancient Greece and Rome, rather than Christian societies and culture.

“However, at the time of UCL’s construction, neoclassical architecture was a popular style for institutional buildings – the General Post Office and the Bank of England are also strong examples. So that secular connection isn’t insignificant... but it is probably overstressed.”

View of the Wilkins Building from the north-east in 1940, showing the bombed-out north range and the dome, before a major post-war restoration overseen by Professor A. E. Richardson, UCL’s Chair of Architecture. © UCL Creative Media Services

View of the Wilkins Building from the north-east in 1940, showing the bombed-out north range and the dome, before a major post-war restoration overseen by Professor A. E. Richardson, UCL’s Chair of Architecture. © UCL Creative Media Services

View of the Main Quadrangle from the east c.1980, when it was still used for car-parking, showing the unfinished South-West and North-West Wings. © UCL Digital Media

View of the Main Quadrangle from the east c.1980, when it was still used for car-parking, showing the unfinished South-West and North-West Wings. © UCL Digital Media

UCL’s Wilkins Building, west front in 2024. Built in 1827–9 to designs by the architect William Wilkins as the first stage of his masterplan for a grand quadrangle in Gower Street. © Photograph by Chris Redgrave

UCL’s Wilkins Building, west front in 2024. Built in 1827–9 to designs by the architect William Wilkins as the first stage of his masterplan for a grand quadrangle in Gower Street. © Photograph by Chris Redgrave

“We’ll be tracing the adaptation and construction of UCL’s buildings in parallel with changes in education, society and technology. We’ll also be addressing some significant gaps in knowledge and clearing up some misapprehensions, too.”

Dr Amy Spencer, The Bartlett School of Architecture

Old answers to new challenges

Amy and Colin are also hoping to highlight some of the entertaining oddities that lie behind the facades of some of UCL’s best known buildings – for example, an ancient Tudor niche in the Geography department in the North-West Wing, which was The Bartlett’s home from 1913 until 1975, when it moved to Gordon Street.

The story of the Bloomsbury Theatre is another one that Colin and Amy are keen to share.

“When it was designed in the 60s, it was going to be a colossal building, with student union sports facilities and all sorts of things,” says Colin, “taking up almost the whole of Gordon Street.

“It was a time of real optimism, when there was lots of cash around to build things like this. But by the time the theatre was going up, there wasn’t as much money, so they never got beyond phase one. So above the Bloomsbury Theatre, believe it or not, there’s a full-size rowing tank, a gymnasium, all sorts of stuff.”

Amy reflects, “At the moment, there are questions about how universities are going to support their estates when many are facing financial difficulty. The story of the Bloomsbury Theatre is interesting because it shows that we’ve gone through this kind of expansion and contraction cycle before. There are lessons to learn, here, and parallels to consider, which highlight the interest and relevance of the Survey’s monograph.”

About the authors

Dr Amy Spencer

Research Fellow, The Bartlett School of Architecture

Amy Spencer is an architectural historian working on the Survey of London. She joined the Survey of London in 2015 and, over the last ten years, has been involved in every aspect of the Survey’s work, including research, fieldwork and writing.

Colin Thom

Principal Research Fellow, The Bartlett School of Architecture

Colin Thom is Director of the Survey of London, where he has contributed to the research, writing, editing and production of the Survey's renowned series of volumes on London's history and architecture.

The Bartlett in London: celebrating 200 years of UCL

This story is part of the Bartlett in London series from the UCL Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment.

In celebration of UCL's bicentenary in 2026, this series of stories explores our impact on the built environment of London – from creating healthier and more sustainable living, to supporting local communities and documenting London’s rich history.

Produced with support from the UCL Innovation and Enterprise Faculties Innovation Fund.

Learn more about Architecture and Historic Urban Environments MA

This programme pioneers a fresh and critical approach to architecture and historic urban environments. Using London as laboratory for learning, students are encouraged to interrogate the past through a rigorous analysis of the present, identifying and addressing historical inequities – environmentally, racially, spatially and socially – ingrained in the urban fabric and common to all cities.

Story produced by All Things Words

© UCL The Bartlett 2025

This story was produced with support from UCL Innovation and Enterprise Faculties Innovation Fund.