Podcast:The housing threat posed by permitted development

Conversions of UK commercial buildings into housing through permitted development may have significant health and social impacts - what are the potential effects?

In the pursuit to solve the housing crisis in the UK, could the cure of using permitted development bring its own hidden issues?

Julia Thrift, Director, Healthier Place-making at the Town and Country Planning Association, joins expert researchers Professor Lauren Andres and Professor Ben Clifford from The Bartlett School of Planning to discuss how there is a wider cost to society that we can’t ignore in this pursuit of solving the housing situation in the UK.

Listen to the podcast

Photo by Arno Senoner on Unsplash

Photo by Arno Senoner on Unsplash

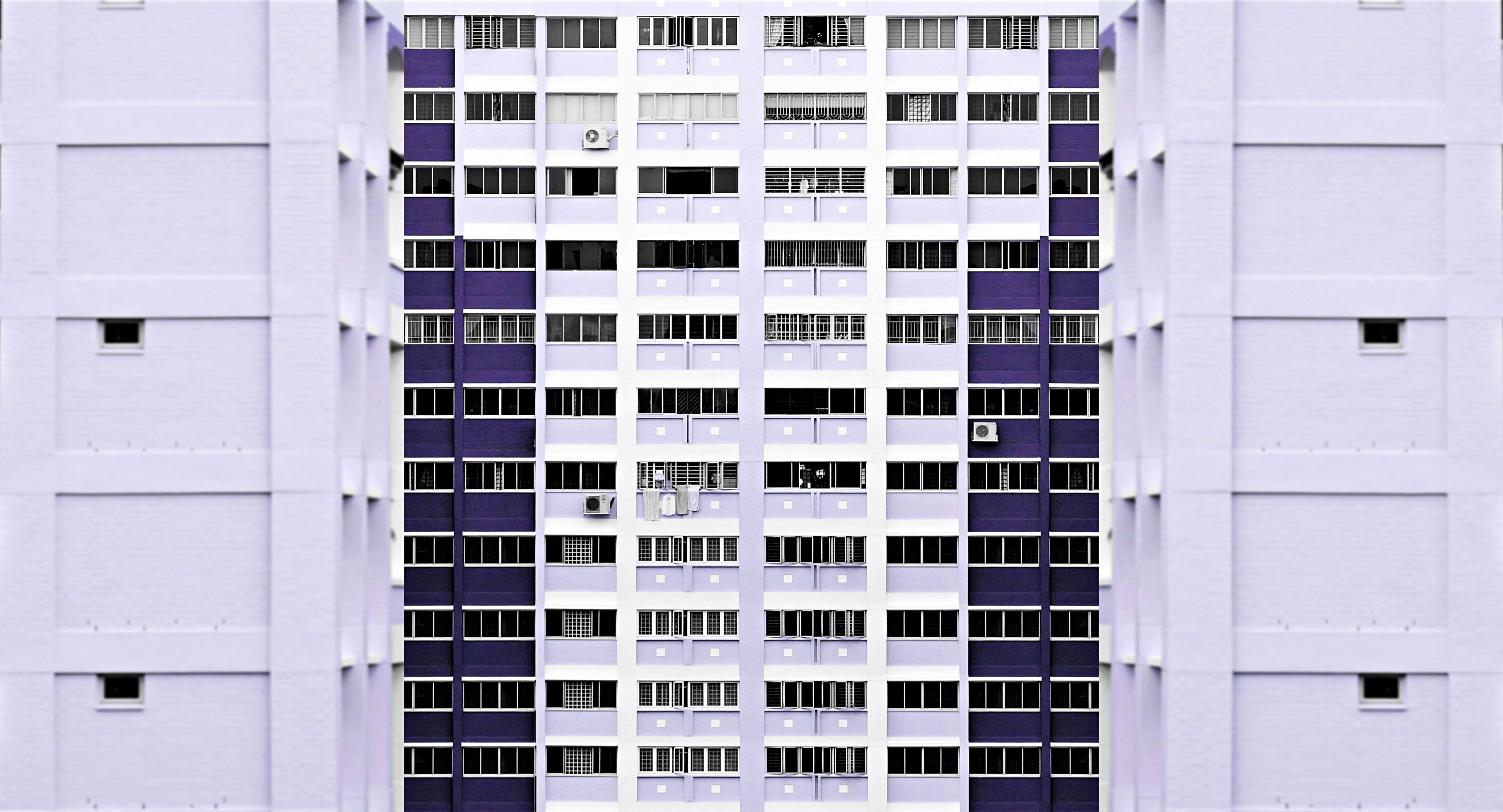

Photo by Danist Soh on Unsplash

Photo by Danist Soh on Unsplash

Transcript

Prof Lauren Andres:

This is a podcast for the Bartlett Review, sharing new ideas and disruptive thinking for the built environment, brought to you by the Bartlett faculty of the built environment at University College London.

Julia Thrift:

And I think you have to ask why would we want to create places that make people ill when we're struggling to pay for the NHS at the moment?

Prof Ben Clifford:

I think it would be better just to have an, in fact, more straightforward just to have a level playing field, anything that creates a new house, a new dwelling that requires planning permission.

Prof Lauren Andres:

Hello, my name is Lauren Andres. I am director of research at UCL's Bartlett School of Planning and Professor of Planning and Urban Transformations. Today we are going to talk about how existing commercial buildings in the UK are being converted to create new housing, so preventing the planning system through permitted development, and more importantly, the dramatic impact of those conversions from a health perspective. When I say converted buildings, I don't mean someone who lives in a luxurious barn conversion property. I mean former commercial buildings like shops, offices, and factories which are being turned into cheap homes, especially in urban areas as the Labour Government is looking to reform and relax our planning system and create more affordable homes. Is this type of development really the best solution for people who need affordable housing? Could permitted development be delivered differently? I am delighted to be joined today by Professor Ben Clifford, my UCL colleague at BSP and a specialist in spatial planning and governance. Ben is leading a major research project funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research. This project investigates the health and wellbeing implications of planning, deregulation for what is called permitted development. I am also joined by Julia Thrift from the Town and Country Planning Association. Julia is director of Healthier Placemaking for the TCPA. The TCPA is a charity that campaigns for homes and places where everyone can thrive. Welcome to you both.

So just to start the discussion, what is permitted development and why has the UK seen a rapid growth in the use of converted housing of this type? Ben?

Prof Ben Clifford:

So ever since 1947 when the then Labour government introduced the Town and Country Planning Act, development rights were nationalised. So what that means is if you wanted to undertake any type of development, you had to get planning permission. That's permission granted by the local council thinking about the principle of the development its design, and that applies both to building new buildings, but also significantly changing the use of existing buildings. At the same time, because there's so much development that takes place to try and stop the system getting clogged up with lots of small matters, certain things were categorised as what's called permitted development, which means they didn't need planning permission. So if you think about putting up a shed or a conservatory, it's quite minor. It's not going to have big impacts, and so you shouldn't have to have planning permission for that. What happened in 2013 is that the government extended the definition of permitted development to include converting offices to residential use, and then in 2015 they added other types of commercial buildings like shops and light industrial units and so on. So that means that these schemes aren't having to get planning permission from the local authority. Nobody's thinking about the principle of development or the detailed design because it's held that it's permitted development, and so only some very minor technical checks are conducted for these schemes.

Prof Lauren Andres:

So really Julia, why is permitted development programmatic? Why is it different from normal planning?

Julia Thrift:

Well, council's give planning permission when the proposal, the proposed development fits in with the local plan for the area, and councils do a lot of research to find out what the area needs in terms of jobs and homes and facilities. And so they will give planning permission if the proposed development fits in with that and not if it doesn't, for instance, as an example, the council might know that what's desperately needed in their area are homes that are big enough for families. So two or three bedroom homes, and perhaps what isn't needed in the area are lots and lots of tiny little one bedroom flats or studio flats. With permitted development the council doesn't get involved to any degree at all. As Ben said, they have to give a few minor technical checks so a developer can come along and say, well, here's a big building.

It's empty at the moment. I want to turn it into a hundred tiny little flats. And the council can't say no, even if they don't need lots of tiny little flats in the area, or even if it's in completely the wrong location, it could be in the middle of an industrial estate with lots of lorries coming and going, and if one building in the middle of that estate is turned into lots of little flats, there may be children playing in the car park with the lorries coming and going. There may be no schools nearby or no shops nearby, or no launderettes nearby, and no way of doing your washing. Councils usually have a sort of quality control role, and that quality control has just gone through permitted development.

Prof Lauren Andres:

You mentioned location. Are all cities across the UK and England affected in the same way? Are there any hotspots? So for example, cities where there's a large number of conversions. Ben, are you aware of it?

Prof Ben Clifford:

Yeah, so it applied across the whole of England doesn't apply in the same way in Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland because planning's a devolved issue. It can be seen everywhere. So you'll find every single local authority in the country has had some of these permitted development conversions. But there are definitely hotspots with the level of housing need around London and the Southeast. There's more schemes in urban areas just because there's more buildings to convert in the first place. And at the same time, there's some interesting sort of hotspots. So there's places that had quite a large stock of office buildings from the 1960s, seventies, which were largely surplus to use, and so we have lots of those. You've tended to see lots of conversions. So an example of that might be Croydon or some of the new towns like Harlow or Crawley, they're near London. There's housing demand, but there's also this supply of large office buildings.

Prof Lauren Andres:

You've just mentioned housing need, and I do have a question, which I guess resonates a lot for politicians. Is any poor housing home better than no home then and why these developments are being set up to fail losing money for local authorities with developers keeping the profits? Julia.

Julia Thrift:

There obviously is a housing crisis and people are in desperate needs of homes, but poor quality homes make people ill, and that's been known for hundreds of years. If we create homes today, they should be good quality homes that will be there for hundreds of years. The research shows that poor quality housing currently cost the NHS about 1.4 billion pounds a year in terms of treating people who live in poor quality housing. But the wider cost to society is more like 18 and a half billion pounds a year, and that's when you take into account things like the mental health problems. Children perhaps can't get to school very easily or can't do their homework in tiny cramped places. There are social care implications. So what's happening, the developers are making additional profits through these poor quality homes, but the state is having to pick up the bill in terms of the longer term cost to people's health and welfare. Not all permitted development homes are terrible or in a really bad state, but some of them are really, really atrocious. And I think people don't realise

Prof Ben Clifford:

Local authorities do have some powers around housing enforcement, but because of austerity, local authority capacity is very, very small. So you can find homes that perhaps wouldn't meet things like the Decent Home Standard, and yet the ability for local authorities to actually take enforcement action is quite constrained just because of a lack of resources.

Prof Lauren Andres:

Your research currently is bringing amazing amount of new data. Can you just tell us a bit more about it?

Prof Ben Clifford:

Yes. Yeah, so previous research had identified some of the common design issues that permitted development homes experience. So permitted development homes can be very good quality, as Julia said earlier, but they can also be very poor. A lot more is at the whim of the developer. And so we found issues with really small space standards. We found issues with, there were some flats that had no windows at all. That was thankfully quite rare, but quite common for there to be a window you couldn't see out of properly or some rooms that didn't have much light. Those two issues have been addressed by government, but there's lots of other issues still. A lot of the flats are what we call single aspects. So they only have windows facing one way. There's not a good mix of different types of housing. There's no provision of outdoor space or there's no requirement for it.

So lots of developers aren't providing that. And so the current research project is trying to find a bit more about the extent of those problems. We are putting some monitor equipment in some homes, for example, to monitor their air quality and their temperature through the year. We're doing a survey with residents to find out who lives in these homes, what's their own perception of their health and wellbeing, and thinking about the consequences from that. So the project will keep going till 2026, but we are starting to gather the data now and very well advanced with that actually. And we're starting to produce interim findings, and we are working with a range of partners, including central government to make sure that they're aware of our findings. There isn't a data set that exists at the moment about where all this housing is nationally. We will produce that. We will also produce a series of guidance documents, so there's a guidance document that we're going to produce for local authorities, thinking about the regulatory levers that are still available to them and how best to utilise those. We're also going to produce a guide for residents and landlords that tries to think about some more everyday practical interventions that could be made to try and improve the quality of life within these homes.

Prof Lauren Andres:

How is the current government reacting to your suggestions and really to the need to rethink permitted development?

Julia Thrift:

Well, we are recording this at the end of 2024, and the government is still relatively new and they're looking at lots of different things, including planning. We don't yet know what they think specifically about housing created through permitted development. We hope that they will consider it and recognise that it is causing problems. So they're looking at lots of different aspects of planning, and we will wait with interest to see what they say about permitted development housing.

Prof Lauren Andres:

I mean, what does it tell us really about the ability, our ability to plan for healthy places and to keep people healthy, Julia?

Julia Thrift:

Well, the planning and public health came from the same roots in the late 19th century when it became clear that the cities that had grown very rapidly during the Industrial Revolution, although they provided lots of jobs and opportunities for people, they also provided some really terrible living conditions, cramped places, no access to green space, and that there was a big effort throughout the late 19th century and early 20th century to create places that would enable people to live healthy lives, and so decent quality council housing, local parks, swimming pools, all of those things that help people make healthy choices were very much at the forefront of planning. And that slightly got lost towards the later part of the 20th century. But I think there's been a big resurgence in the recognition that planning is foundational to good public health. If people don't have a decent place to live with access to friends, to jobs, to green spaces to clean air, then that has a huge impact on their ability to live a healthy life. So just as we are rediscovering those links, it's particularly sad that there's this route to bypass planning and create unhealthy places or places that are potentially very unhealthy.

Prof Lauren Andres:

This is hugely problematic indeed. I mean, if we are looking at the current governmental agenda, what does it tell you really in regard to this debate between housing quality and housing quantity?

Julia Thrift:

I think it's really Interesting. We've got a new government. They have made two very strong commitments. One commitment is to build 1.5 million new homes during this parliament, and the other commitment is to have a health mission to focus government action on creating what they described in the Labour Party manifesto as a fairer Britain where everyone lives for longer. And since the government came into power, the thinking around that health mission has become much more focused on what's called prevention, preventing poor health. So I think the government's going to have to think very carefully about their understandable focus on developing 1.5 million new homes. If they only focus on the number of new homes and they don't focus on the quality, then they're going to really undermine their health mission.

Prof Ben Clifford:

I think there's this sort of rhetoric that's become quite widespread now that just views planning as a barrier to the supply of new homes. And like any regulatory system It can be and it can act as a barrier, but I think we need to have a slightly more sophisticated discussion that thinks about the benefits as well as the costs of regulation. And so the housing crisis is multifaceted. The reason we don't have enough homes at the right type and the right location, the right affordability is down to many, many factors, not just the planning system. And we have to think about some of the benefits that can come from planning regulation in ensuring a basic standard for that quality given the sort of health implications Julie was just talking about.

Julia Thrift:

There's a sort of popular myth that not enough planning permissions are being given, and that's why we don't have enough new homes. But in fact, the planning permissions are being given to deliver all of the homes that the governments have wanted to create. The problem is the homes aren't being built. So the very simple narrative, 'Oh, planning stops houses being built.' isn't actually true. So when permitted development is put forward as a way of 'Planning's preventing new homes being created, let's have permitted development', I think the diagnosis of the problem is wrong. Many of the house builders don't rush to build lots of homes. If they did that, the price of homes would drop and their profits would drop. So permitted development is being put forward as a solution to a problem that perhaps isn't actually there. It's a different problem that needs solving.

Voice Over:

This is the Bartlett Review podcast, sharing new ideas and disruptive thinking for the built environment. When we're looking at permanent development, I mean we are effectively talking about adaptive reuse. I'm interested to hear your thoughts about if we could do this differently, and especially if you have examples elsewhere across Europe, for example, where they can do it in the right way.

Prof Ben Clifford:

Yes. Yeah, I mean, adaptive reuse in general is a good idea. There's a lot of what we call embodied carbon in buildings. So if you think about the sort of structure of buildings, all of that concrete, there's actually a lot of carbon that's got into that. The construction industry is a huge emitter of greenhouse gases. And so what we can do to reduce that is looking at things like adaptive reuse and changing buildings that are suitable to be converted in the right location into other uses. So the principles fine, it's just about how you govern it, I think to ensure some very basic standards. If we look internationally, there are examples is a huge amount of interest in this. Now, particularly after the pandemic, when there's been a rise in hybrid and homeworking and office vacancy rates have increased in many, many countries across the world. So there's growing interest, but other places have got better basic standards. So we could go to, for example, the Netherlands where instead of lots and lots of deregulation that the government took a different approach there. It tried to encourage these type of conversions, but doing so by use of things like best practise, what does a good conversion look like? Giving local authorities a proactive role to say, this is where conversions should take place. This is where conversion shouldn't take place.

Julia Thrift:

Our planning system is very weak in terms of the way it considers the environment, and one thing that it completely ignores is embodied carbon. So when councils set out their local plans, they don't have to have a carbon budget with those local plans, and that means that it becomes easier just to knock things down and build a new building rather than to think about how can we effectively turn this old building into a good quality new building. And because there isn't that motivation in the planning system, it means that we are really not terribly focused on how to convert buildings well. We absolutely have to use the buildings we've got because we just cannot afford to waste all the embodied carbon by knocking lots of things down and rebuilding, but we have to make sure it's done to a good quality.

Prof Lauren Andres:

If you were to find yourself in a lift and meeting with one of the ministers, and you would have to pitch for really the key changes that would need to be made in the UK planning and legislative system, what would you like to say in relation to how we have been approaching permitted development to date, but also how we really need to address health in planning? Ben?

Prof Ben Clifford:

I think I would just say for anything that creates new housing, given the important link between housing and health, it should go through the ordinary route of planning permission. Permitted development actually skews things by having the very existence of this route with less regulation, no requirements for things like affordable homes, et cetera. It sort of unbalances everything. And I think it would be better just to have an, in fact, more straightforward and less complex just to have a level playing field. Anything that creates a new house and new dwelling that requires planning permission. But of course, we think about things we can do to ensure that the planning system generally is working in a much more efficient way.

Julia Thrift:

I think what I'd say to the minister is national planning policy should start with a really strong statement saying that the purpose of planning is to create places where people can live healthy lives and that meet the needs of climate change. At the moment, national planning policy does talk about healthy placemaking, but it's really not a priority. It's something like paragraph 90 or something. And I think you have to ask why would we want to create places that make people ill when we're struggling to pay for the NHS at the moment? In terms of permitted development, I think we should just go back to where we were pre 2013 where permitted development couldn't be used to create homes. It's not a suitable way of creating homes. They should go through the planning system with all the quality control that that includes.

Prof Lauren Andres:

Looking at what is happening now with local authorities, they are facing increasing financial pressures. I mean, we look at Nottingham Birmingham , Woking Council they have all filled a Section 114 notice in 2023 meanings, they're basically going bankrupt. What does it tell us on how local authorities can really address this issue? And also just act and support communities in need.

Julia Thrift:

When homes are created through permitted development, the developer doesn't have to pay a contribution towards local infrastructure. And that's one of the reasons some developers might like it because it increases their profits. Usually when, for instance, if a developer says, I want to develop 300 homes, the council would say, well, we need some funding to provide the things that the people who live in those homes will need. So that might be money for parks or schools or money for new affordable housing in the area. When homes go through permitted development, the council doesn't get that money. So councils are actually losing out on millions of pounds because of permitted development. So it does have financial implications at a time when councils are struggling to provide the people who they need for processing planning applications, or as Ben said earlier, for checking that homes that are of a habitable standard councils need that money and it shouldn't be denied to them by allowing developments to go outside the planning system.

Prof Ben Clifford:

I think it's also worth adding as a sort of cherry on the top of that, that actually the fee you pay, so there's a notification process to go through for permitted development. So the council can do the technical checks that they do still need to do, but the fees for that are much, much lower than planning permission. So the council itself for the work of their own planning offices is losing out before we even get to the contributions towards infrastructure or affordable homes. None of these homes through permitted development need to be formally affordable housing either.

Prof Lauren Andres:

I wonder if you could tell us more about the type of developers going through those type of permitted development and also what it means in term of how they're selling the units, renting the units, and how they are maybe working with housing associations.

Prof Ben Clifford:

So they're not the traditional large house builders. The traditional large house builders have a certain model, which is basically new build as far as possible on a greenfield site. It tends to be what we call SME, small medium enterprise developers, some of whom have sort of built a business model around the opportunity through these conversions. In terms of what happens once they're built, the poor quality schemes are not mortgageable. So actually mortgage lenders themselves have rules about what they're willing to lend on. The ones that are really poor quality couldn't be sold. So what's often happened is they've then sold the entire conversion to another landlord, and that other landlord is then renting them out. They may be renting them out all individually, directly to people on a private basis, or they may be using them for what's called temporary accommodation. And unfortunately, some of the really poorest quality have been used for that temporary accommodation. What we're not seeing, I'll just add, is people like housing associations who tend to have higher basic standards for housing that they're willing to rent out, that they're not usually involved in these other smaller private landlords.

Julia Thrift:

I suppose what I'd say is that all developers need to make money, obviously, or they'll go bust and then they wouldn't be developers anymore. So every developer needs to make sure that if they develop a building, it will make a profit for them so they can keep going. However, lots of developers also want to contribute to the places where they work. They want to create good buildings that are good homes. They want to have a legacy. They want to be able to look at somewhere and think, yeah, we did that, and it's providing lots of good housing. Those developers, I think, are unlikely to go through permitted development. They just go through the planning system. Why not? So I think it tends to attract developers who are entirely in it for the money. And certainly over the last six months at the TCPA, we've been talking to people in councils around the country about their experience of permitted development. And some of the feedback we've had is that it does tend to attract the cowboy developers, for want of a better word, because they just want to make money, turn a quick buck, sell it on, and they don't really care about the quality.

Prof Ben Clifford:

I think that then impacts others. So during one of my previous rounds of research, we had a case study in Leicester, and I remember hearing from a developer who used to do conversions, because of course you could do conversions long before permitted development came along through full planning permission. And this was a local developer who did actually specialise in these conversions, doing them to a higher quality, and said, after permitted development came in, it was actually harder for him because if he was going to try and do things to a higher quality, he'd get outbid for the sites from those who are willing to do them to a much lower quality and therefore could actually afford to pay more for the office building so that the very presence of this deregulated route then affects other developers who might want to do slightly better schemes too.

Prof Lauren Andres:

So really need, just to conclude the podcast, is there hope in the sense that, is there any good practises that could be mentioned, but also is there hope because we have a new government in place and we hope changes are going to be made?

Prof Ben Clifford:

I think there's a few reasons for hope. One is that conversions can be done well, and there are examples, particularly those that have gone through planning permission still. So for example, near us here in Holborn, in Central London, there was a conversion called the Parker Tower that did go through planning permission, but it showed how a sort of sixties large office building could be converted very well flats that are dual aspects. So windows facing two directions, balconies were put in, communal facilities have put in, we can find examples where there's roof terraces, things like that, that really benefit the residents. I think there's definitely hope that a new government is looking at policies again, and it'll be very interesting to see where they come when they do come to a view on permitted development, but now being able to take a view, I think hopefully with the benefit of lots more evidence.

Julia Thrift:

Yeah, I think there's definitely hope. And the thing that struck me over the last six months or so is that there's now widespread recognition that we have a problem of ill health in this country, and it's affecting the economy, particularly younger generations, the people who should be entering the workforce full of energy and optimism. Many of them are actually not very well, and this is now really recognised by the private sector. It's recognised by the NHS that they're having to treat people with avoidable illnesses. And I think it's becoming increasingly recognised that poor quality homes is one of the factors that's causing some of this ill health. And the other cause for optimism is that there's an increasing focus among architects and designers and councils starting to think about how we create places within our carbon budget, and that means good quality conversions. And I think over the next few years, we'll see an increasing number of good quality conversions that will inspire others to do the same.

Prof Lauren Andres:

Thank you, and many thanks to you both for this absolutely fascinating discussion, and I wish you all the best in your research and in all the work you're doing on this topic. Thank you, Lauren. Thank you. And to conclude for more information about the Bartlett School of Planning, which is part of the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment at UCL, you can visit our website, ucl.ac.uk/bartlett, or follow us on X @BartlettUCL.

About the speakers

Photo by Breno Assis on Unsplash

Photo by Breno Assis on Unsplash

The Bartlett School of Planning

At The Bartlett School of Planning, we offer a unique hands-on learning environment guided by urban planning experts and practitioners at the forefront of our field.

Podcast produced by Adam Batstone

© UCL The Bartlett 2024