Understanding the UK’s left-behind places

New research is exploring why ‘left-behind places’ exist, and how to help these communities

The divisions have become impossible to ignore.

In the wake of the UK's 2016 Brexit referendum, governments, policymakers and academics belatedly connected the shock result with its origins in the economic and social disparities between different regions and social groups across the UK.

The government’s 2022 white paper, Levelling Up the United Kingdom, specifically addressed the areas that felt ‘left behind’ - places that had suffered due to regional inequalities.

Yet in the rush to rectify these issues, politicians and policymakers risk misunderstanding the complex conditions affecting the diverse communities gathered under this umbrella term of ‘left-behind places’ (LBPs).

Understanding a ‘left-behind place’

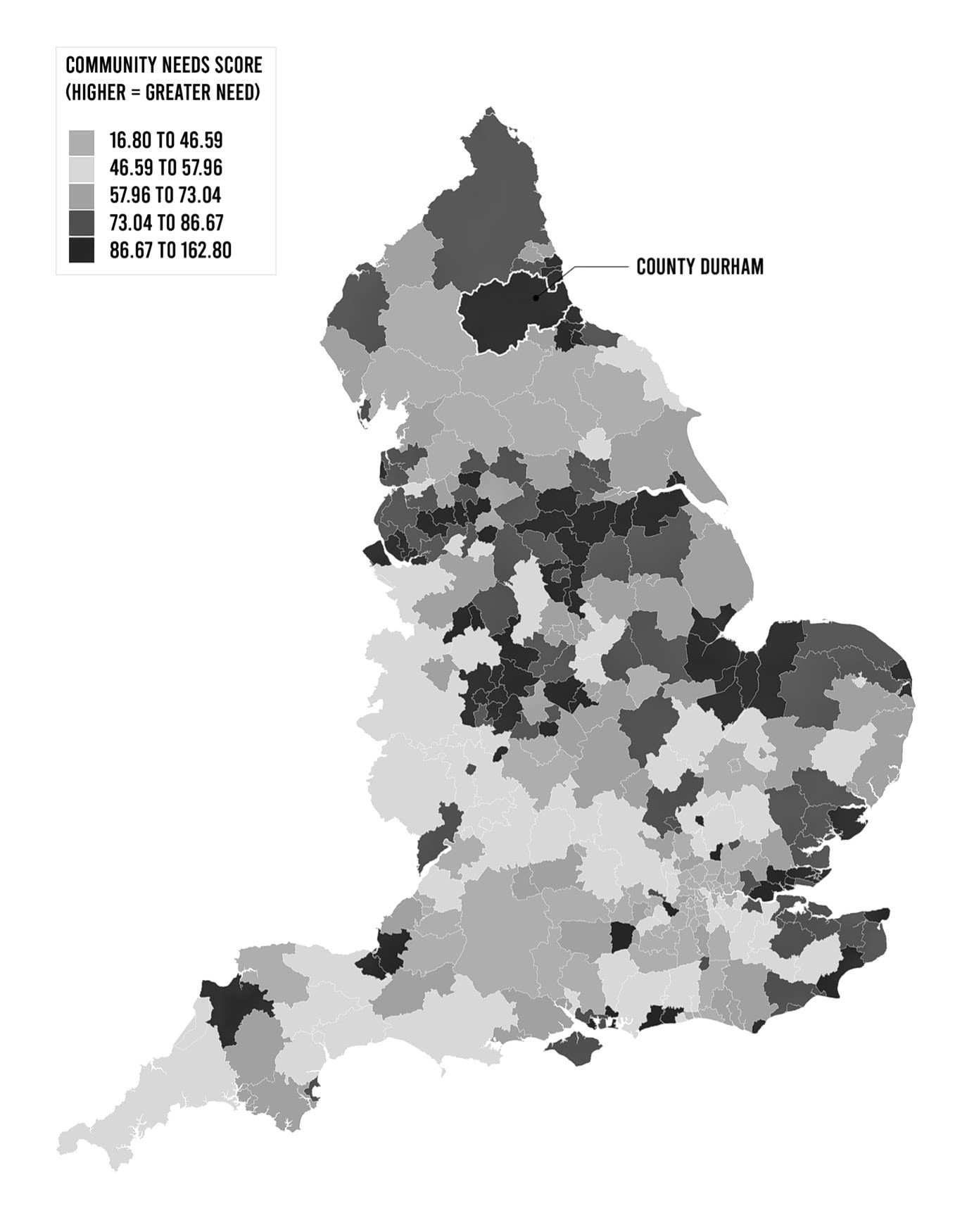

“There’s been an explosion of research about ‘left-behind places’ – in the UK, the US, and other places.

“Much of that research has been about quantifying the extent to which places have been left behind - as defined in socio-economic terms, according to conventional indicators”, explains John Tomaney, Professor of Urban and Regional Planning at the Bartlett School of Planning.

“We saw a gap... there was much less work delving deeply into left-behind places to see what it was like to live in them. So rather than looking at lots of places and comparing them, we wanted to look in detail at one place to understand more the processes at work producing these outcomes.”

John has worked as part of a UCL and Durham University research team, along with Maeve Blackman, Lucy Natarajan, Dimitrios Panayotopoulos-Tsiros, Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite and Myfanwy Taylor, to produce a deep place study titled ‘Social infrastructure and ‘left-behind places’.

In this case study (and the report that preceded it) the team worked with the residents of Sacriston, a former mining village in northern England to explore the ‘making, unmaking and remaking of social infrastructure (SI)’ in left-behind places.

“We wanted to look in detail at one place to understand more the processes at work producing these outcomes.”

Map of the UK overlayed with Community Needs Index scores. Source: OCSI and Local Trust - Local Insight

Map of the UK overlayed with Community Needs Index scores. Source: OCSI and Local Trust - Local Insight

Digging deeper in Sacriston

There were several reasons to choose Sacriston for the study. Chief among these was Sacriston’s unique status as the location of the last working coal mine to close in inland County Durham.

“We were interested in the transition from an industrial to post-industrial economy. There are still people there who worked at the pit who you can talk to about that world.”

John’s personal roots in the local area also proved advantageous.

“Many of the villages across County Durham I’ve got family connections with, one way or another. It was really very useful – people would tell me, ‘oh, somebody wrote a history of the pit, it’s all in a big box upstairs’, things like that. It cuts a lot of corners in terms of getting hold of research materials.”

Sacriston Colliery Cricket Club: part of the village's social infrastructure today. Image credit: Carl Watson

Sacriston Colliery Cricket Club: part of the village's social infrastructure today. Image credit: Carl Watson

Sacriston's historic mining community: the people of Sacriston with Lodge banner, Durham Miners’ Gala, 1958. Image credit: Beamish Museum (NEG 73231)

Sacriston's historic mining community: the people of Sacriston with Lodge banner, Durham Miners’ Gala, 1958. Image credit: Beamish Museum (NEG 73231)

Aged Miners’ Homes in Sacriston, opened in 1926. Image credit: Beamish Museum (NEG 84649)

Aged Miners’ Homes in Sacriston, opened in 1926. Image credit: Beamish Museum (NEG 84649)

Redefining the relationship between researcher and community

The research team worked with different focus groups to get a range of perspectives, and conducted oral history interviews with elderly residents to get a sense of how people understood the economic, political, cultural and social changes taking place in Sacriston.

“We never really arrived in this community with a conventional research question. We arrived with the intention of listening to people and finding out what they thought was important.

“And secondly, we intended to find out whether we can be of any use in that community.

“Traditionally the relationship between academics and any kind of community is that you breeze in, get what you need for your academic purposes, and then you leave. Whereas what we’ve tried to do here is establish a long-term relationship with a particular place, to get closer to a deeper understanding of what’s happening.”

“We never really arrived in this community with a conventional research question. We arrived with the intention of listening to people.”

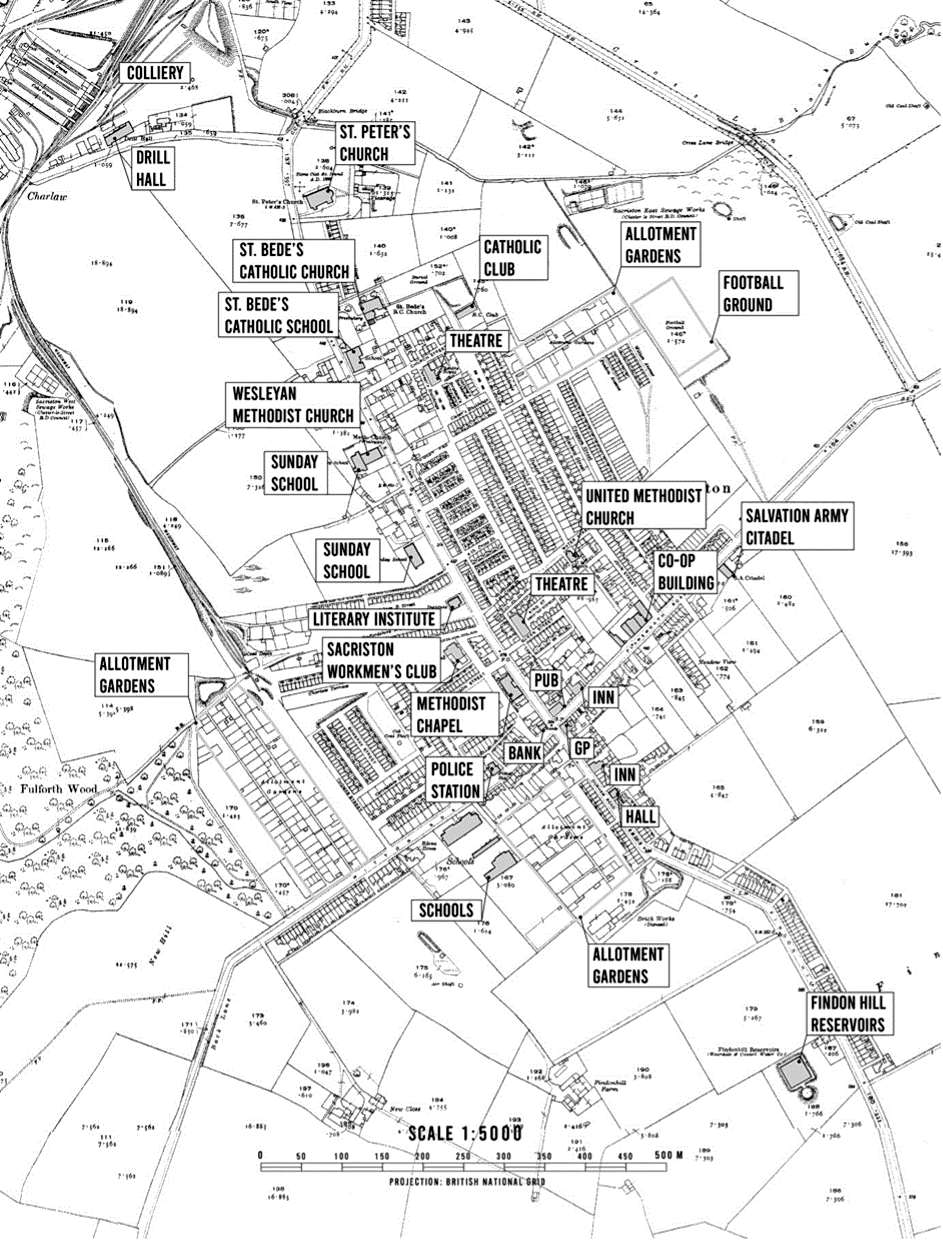

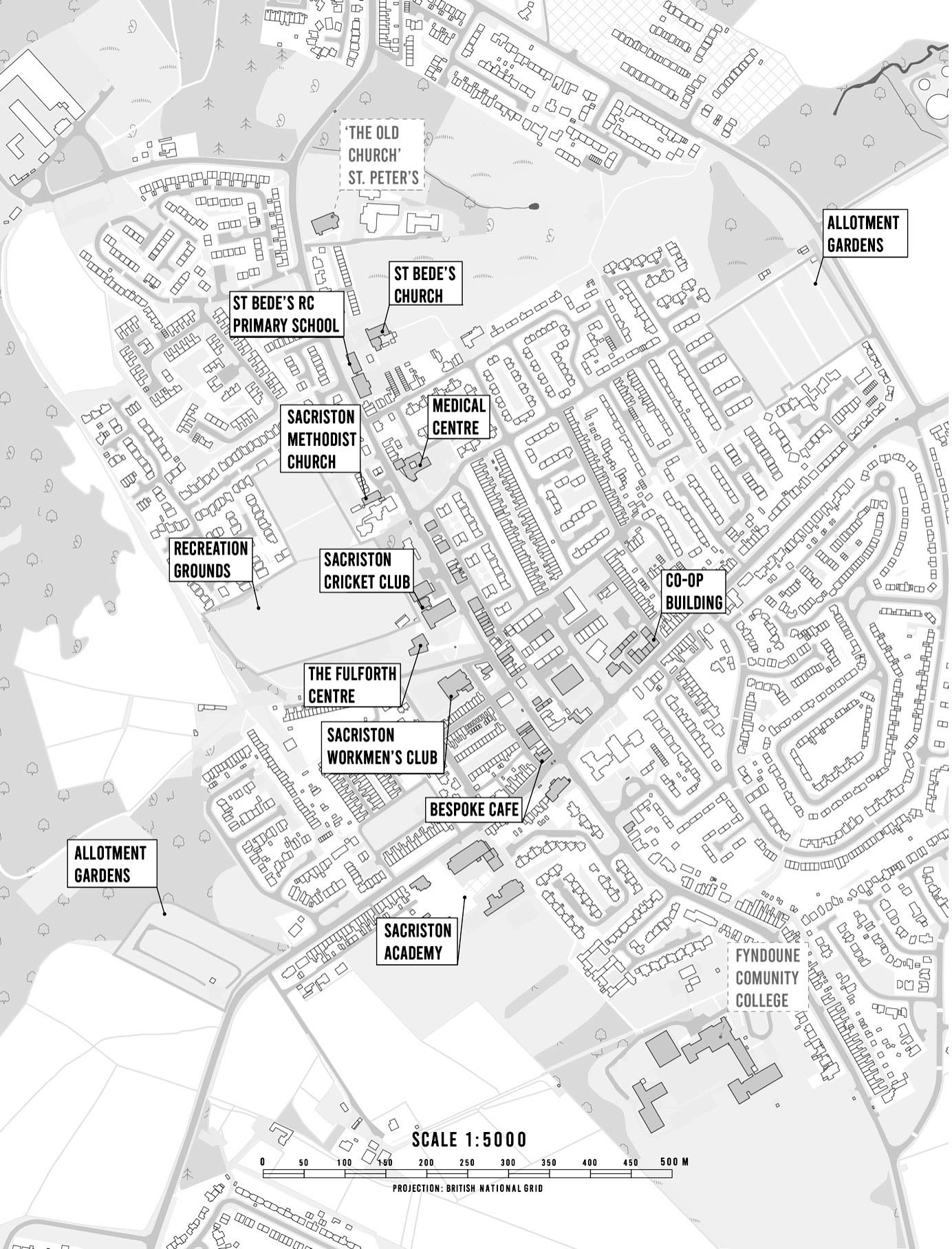

Maps illustrating the change in Sacriston's social infrastructure from 1910 to 2022

Map of Sacriston social infrastructure in 1920. Source: Digimap Historic Roam

Map of Sacriston social infrastructure in 1920. Source: Digimap Historic Roam

Map of Sacriston social infrastructure in 2022. Source: Digimap Ordnance Survey

Map of Sacriston social infrastructure in 2022. Source: Digimap Ordnance Survey

Intersecting changes

The team found that changes in the social infrastructure of the village were key to understanding the other changes occurring in Sacriston.

“There’s more and more academic literature... and policy interest as well. Policymakers are identifying deficiencies in social infrastructure as a key problem in these left-behind places.”

In the report, they highlighted that the changes in social infrastructure were caused by an interaction of both local and wider societal changes.

“Men, women and children...spent much of their leisure time locally. Now patterns of life are different: women have less spare time for informal leisure in their neighbourhoods; children are unlikely to be given the same freedom to roam; families are more likely to drive to leisure activities further away, and rising incomes mean that for a majority, leisure is more commercialised.

“It would be too simplistic to say that Sacriston has undergone economic ‘decline’...many people have more money for commercial leisure activities. Yet this increase in material abundance has some downsides.”

Proactive research approaches to face the Grand Challenges

Funded by the UCL Grand Challenges programme, John and the team are intent on using their relationships with the communities of Sacriston to find solutions and drive change.

“We were very much led by the community, who identified the issues for us, and have helped us produce this research.

“And increasingly, I’m less interested in conventional measures of academic achievement. I’m more interested in whether what we’re doing is actually useful in communities.”

The research team is currently working hard on two different fronts.

Firstly, they’re busy collating their evidence and drawing together a raft of policy recommendations, to show how central and local government can help community organisations remake their own social infrastructure.

Secondly, they’re building on the findings of the report, and supporting the communities of Sacriston and the surrounding areas in whatever ways they can. UCL has provided resources to fund a conference of community organisations that will bring together groups local to County Durham, along with external partners from further away, including representatives from Tottenham’s Wards Corner project.

John himself is now involved in a number of trusts and initiatives, including a close partnership with the Durham Miners Association, which has raised £11 million for the refurbishment and reinvention of Redhills, the Durham Miner’s Hall.

It’s clear to see that this open-ended project has helped John gain a better understanding of the possibilities in the relationship between academics and the communities they study.

“We’ve got involved with some really inspiring people, community heroes.

“You learn a lot from hanging around those kinds of people - not necessarily just in terms of knowledge and information, but in terms of how to behave in a civilised way.”

“Increasingly, I’m less interested in conventional measures of academic achievement. I’m more interested in whether what we’re doing is actually useful in communities.”

About the author

Professor John Tomaney

Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, the Bartlett School of Planning, University College London

Prof John Tomaney has previously held the role of Henry Daysh Professor of Regional Development and Director of the Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS), Newcastle University. He has held visiting appointments at Monash University, the University of New South Wales, Newcastle University, Manchester Business School and University College Dublin and is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Science (UK) and a Fellow of the Regional Studies Association.

Learn more about urban and regional planning

The Bartlett School of Planning is a global centre of excellence in education and research. We offer a unique hands-on learning environment for undergraduate, Master's and research students guided by urban planning experts and practitioners at the forefront of our field.

Story produced by All Things Words

© UCL The Bartlett 2023