Decarbonising London’s social housing

London’s Islington Council has partnered with UCL to decarbonise social housing in pursuit of net zero

The urgency of the climate crisis has not escaped leaders in local government. To reflect their sense of collective responsibility, since 2019 more than 300 councils across the UK have declared a climate emergency.

Many people (including those working in these local authorities) have been left wondering how and when this political commitment would translate into meaningful action.

Looking for a place to start, the London Borough of Islington identified their social housing stock as being a primary opportunity for CO₂ emissions reduction.

“Most of the housing stock that exists now will still be here in 2050,” says Steve Evans, Senior Research Fellow and part of the UCL Energy Institute team commissioned by Islington to help get their housing stock to net zero by 2030.

“We can’t just make newer, better buildings to improve efficiency. New builds are just the tip of the iceberg – to achieve net zero, these existing buildings must have their energy efficiency improved, and they need to stop using fossil fuel to heat them.”

Sizing up the task of decarbonising Islington’s housing

Islington assembled a cross-departmental team to collaborate with the UCL research team, to identify the most suitable technologies and interventions that could be used to retrofit the housing stock. This broad range of expertise made it much easier to quickly assess, select or dismiss potential solutions.

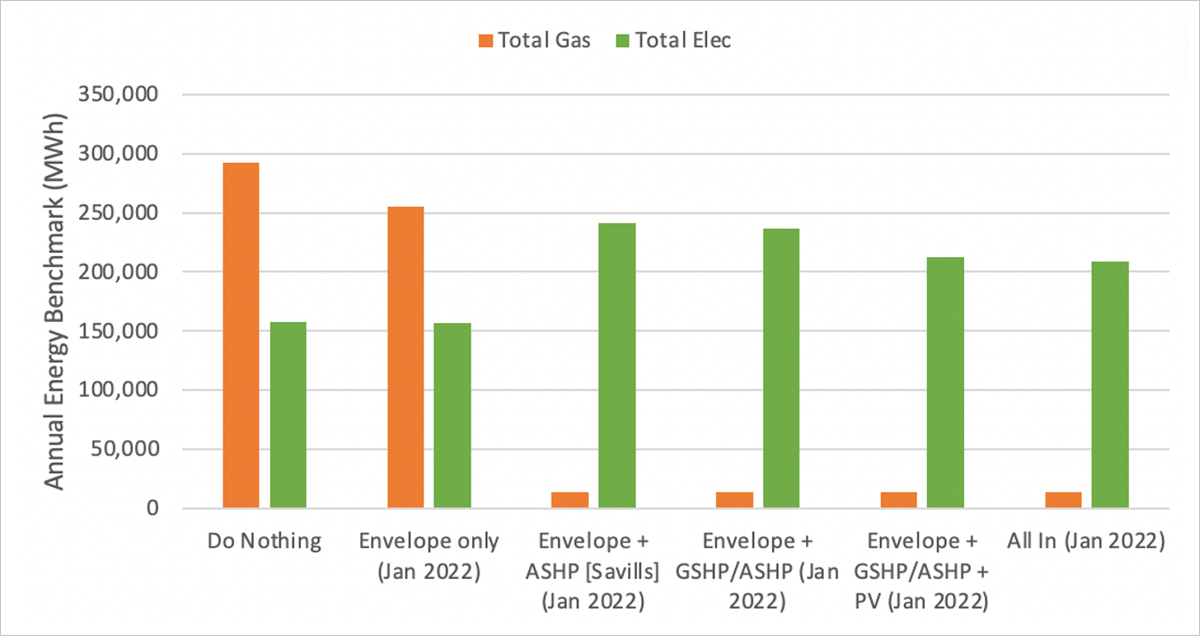

With a basket of effective measures in place, the next step was to set out six different scenarios, or ‘packages’. These ranged incrementally, from a ‘do nothing’ response through to an ‘all measures’ package.

The next task would be to assess the cost implications, energy use and emissions reductions resulting from each of these packages, using tools created by the UCL Energy Institute’s Building Stock Lab.

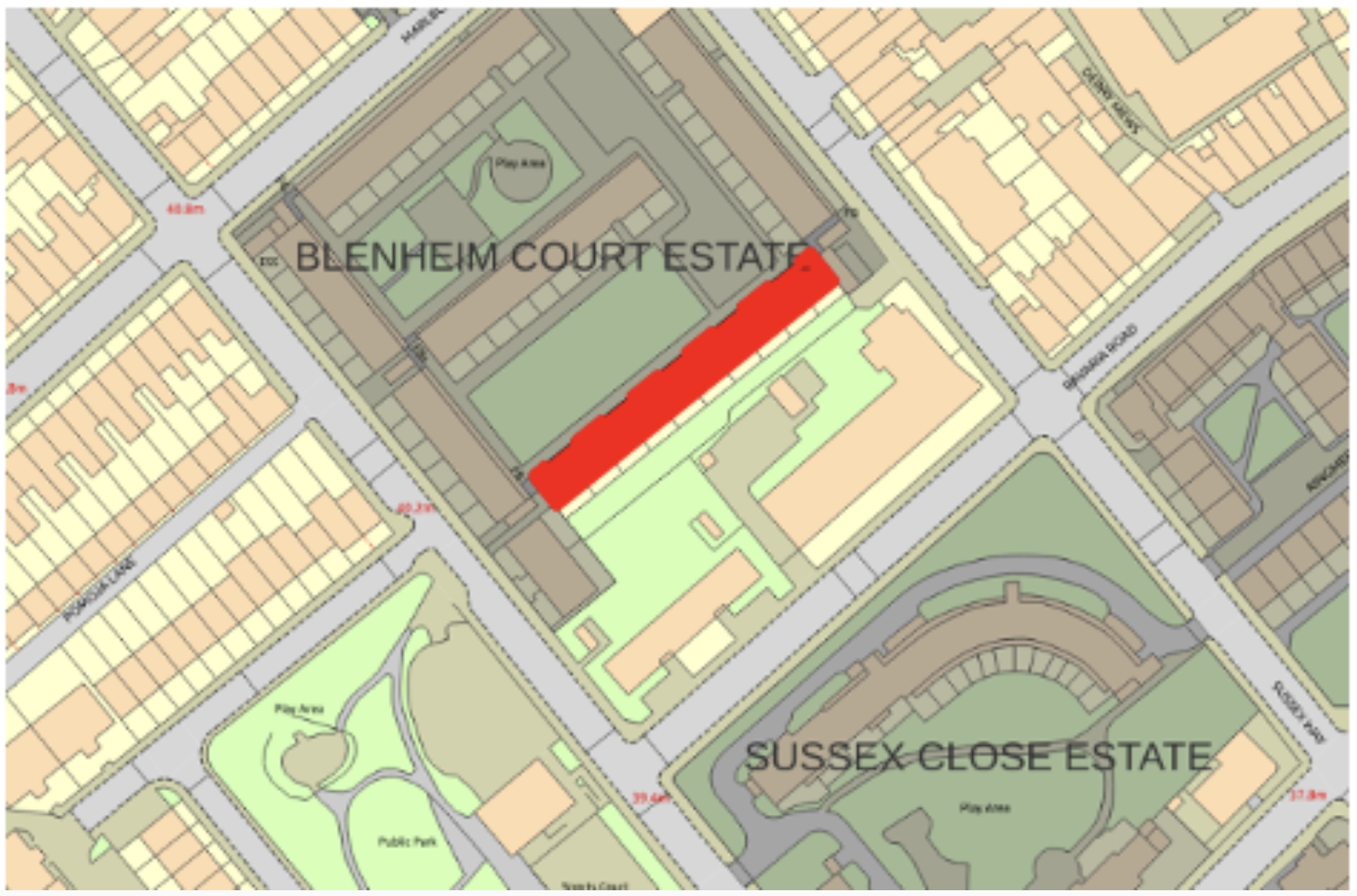

Examples of Islington social housing stock

‘Digital quantity surveyors’

Islington’s housing stock is incredibly diverse. This densely populated area contains everything from 18th century houses in conservation areas, through to 1970s high-rise blocks. To get accurate data about the implications of the packages, the research team needed to bypass standard modelling approaches, which would have aggregated these wildly different types of dwelling into loose-fitting archetypes. They needed to model each individual home.

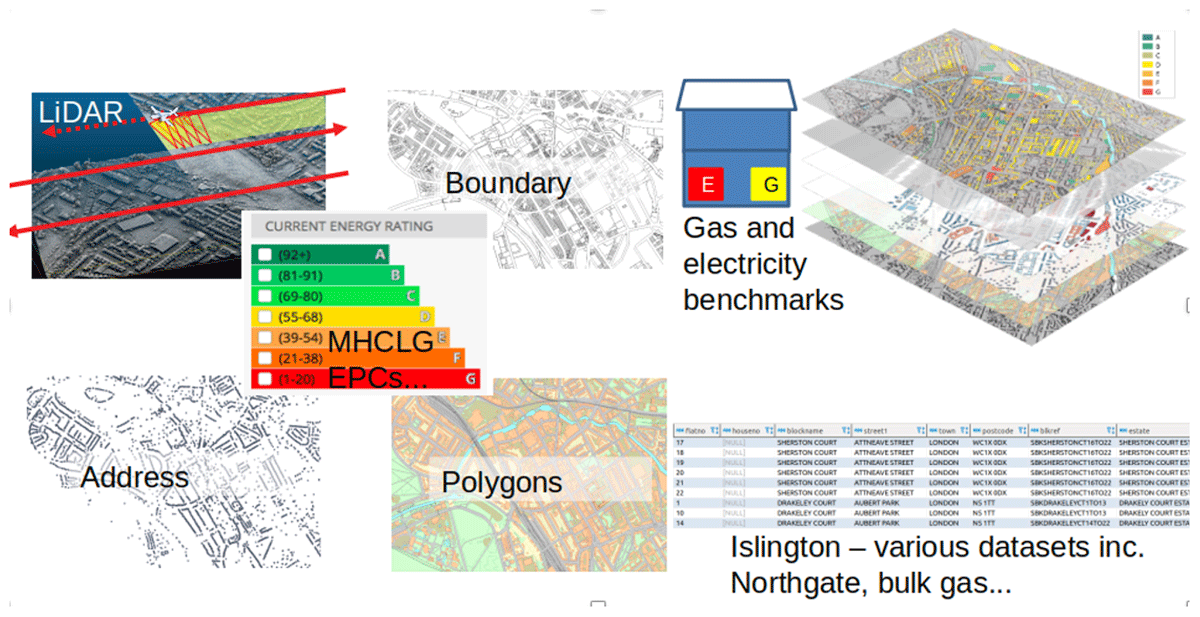

UCL had deployed their 3DStock model in a range of contexts before – notably on commissions from the Greater London Authority, creating the London Building Stock Model in 2018 and the London Solar Opportunity Map in 2019. Using this powerful tool, and drawing data from a range of sources (including Environment Agency aircraft equipped with LiDAR equipment), Steve and the team were able to model every single one of Islington’s 33,300 social housing residences.

Data sources used in the construction of the 3DStock model of Islington, including data supplied by Islington Council

Data sources used in the construction of the 3DStock model of Islington, including data supplied by Islington Council

These sophisticated models of individual homes were equipped with real-world energy consumption data, along with any existing energy-saving improvements, energy performance certificate (EPC) rating, geometry and floor area, and potential for solar photovoltaic (PV).

The data from the 3DStock model was then loaded into a second piece of software – the Pathways to NetZero tool, developed by Daniel Godoy-Shimizu at the UCL Energy Institute.

This allowed the UCL team to simulate each of the borough-wide packages, accounting for the predicted costs and results of retrofitting each individual home. The Pathways to NetZero tool also allowed multiple different considerations to be applied – for example, prioritising homes in deprived areas, or specifying a maximum total spend per dwelling.

Steve characterises the UCL team’s role as that of ‘digital quantity surveyors’, saying:

“The key thing, that we hadn’t really done before, was taking the existing stock (which we’ve been quite good at modelling for a while) and then projecting it forwards to find out what would be required to significantly reduce emissions. Basic things like how many rolls of loft insulation are required or how many double-glazed windows might need replacing?

“The other key thing that made this different was the ability to look at the impact of different types of roll out. You can only do a certain number of retrofits per year, so the order you do those can also influence how quickly your CO₂ emissions come down.

“I always liken it to the COVID-19 vaccine rollouts, where they had to decide who should get the vaccine first for maximum impact. If you tackle the houses with the worst emissions first, then your trajectory is improved – but that might be at the expense of people in fuel poverty.”

In some ways, Islington provided the ideal testing ground for this work. Alongside the diverse mix of housing stock to be modelled, the borough’s exceptional track record in social housing administration meant the UCL team could draw on comprehensive detailed datasets throughout the process.

These included up-to-date surveys listing where properties were occupied by tenants or leaseholders – an important factor when bidding for funding to retrofit social housing, which is often restricted to buildings with a minimum of 70% tenanted occupancy.

“Heat pumps make a far greater impact. Insulating buildings alone won’t get you to net zero.”

Progress built on UCL data

Costs were calculated using several sources, including the cost of recent retrofits in Islington, and extensive advice from Savills, the London-based UK property consultants.

The UCL Engineering Team also made considerable contributions. Professor Jose Torero Cullen (an expert witness on the Grenfell inquiry), Dr Michael Woodrow and Dr Augustin Guibaud were brought in to advise on the fire risks of retrofitting materials, and Dr Valentina Maricioni worked with the team to ensure that mould and damp risks were similarly minimised.

The projected scenarios were all calculated with a 2030 end date, in recognition of Islington’s stated net zero ambitions.

The most ambitious package (combining air-source and ground-source heat pumps, double glazing, insulation and solar PV where viable) was found to potentially bring a 70% reduction in emissions by 2030, at an estimated cost of £1.6bn. Much of the remaining 30% of emissions was found to be outside Islington Council’s control, being largely attributable to fossil fuel usage by the National Grid (although interestingly, increasing use of renewables in the national energy mix meant that even the ‘do nothing’ package saw measurable emissions reductions).

The Council have already put this collaboration with UCL to good use. The report was used as evidence in a successful bid for £4m from the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund (SHDF), and plans are currently underway to retrofit the first 400 homes.

“One of the key things when you go for SHDF funding...they want to know very detailed specifics about your buildings and the measures needed. It’s a real challenge for some local authorities, so the report we wrote definitely contributed to that success.”

One of the most important findings of the report – with ramifications that potentially stretch far beyond Islington – was the relatively modest contribution made by fabric measures (including insulation) to the reduction of emissions. The ‘envelope only’ package, where all properties were retrofitted with double glazing and wall, roof and floor insulation, reduced average gas use by 13%, and overall emissions by roughly 33%.

Resulting expected changes in the use of gas and mains electricity

Resulting expected changes in the use of gas and mains electricity

Steve stresses the importance of this finding, particularly in the context of widespread perceptions of people and organisations across the political spectrum that better insulated homes in the UK will provide the emissions reductions needed for net zero.

“Heat pumps make a far greater impact. Insulating buildings alone won’t get you to net zero.

“You’ve got to focus on emissions reduction, but the official message still seems to be ‘fabric first’, before other measures. Our report argues that a ‘fabric first’ rollout is very expensive.

“There’s a very real risk in some properties that if you put in a heat pump, people can’t be warm enough. But I think that’s led to a confused message, and it’s got people thinking you’ve got to massively insulate before you can even consider a heat pump.

“Whereas in fact, you need improvements, but not to that extent, and it all depends on the building.”

Giving up gas

The ‘fabric first’ misconception is far from the largest hurdle faced by local councils in their journey to net zero.

“The solutions to get to net zero have existed since the 1970s, or longer. Some people are hoping for a ‘silver bullet’ like hydrogen to solve all the problems, but we’d be better off using existing technology and implementing it now, with proper installations by experienced tradespeople.

“But it’s going to require a lot of investment, and this is currently lacking.

“We need more incentives to move away from fossil fuel heating. Until that happens, people will continue to ask, ‘why would I buy a heat pump when a new gas boiler costs so much less?’”

Steve also warns of the dangers of focusing too heavily on EPC ratings as a measure of net zero progress – and confusing this measure of energy efficiency with genuine emissions reductions.

“EPCs are scored on ‘costs of running the home’ rather than CO₂ emissions. As such, they currently penalise an owner who switches from gas heating to electric heating, due to the current price differences. They’ll need some thought and adjustment if they’re going to help us reach net zero.”

Modelling every building in Britain

The Building Stock Lab are busy implementing their methodologies on a number of projects. The tools and techniques used on the Islington reports are being used to simulate district heating provision in other population-dense boroughs.

Other London Councils hope to create heat networks similar to Islington’s (which draws off heat from the London Underground system) to aid their decarbonisation.

The UCL team are also looking at ways to create a more flexible ‘cost calculator’ functionality, allowing councils to more easily update and specify the associated costs of labour, materials and resources used in their retrofits.

One project that will be keeping Steve and the team busy for the foreseeable future is the National Buildings Database, which aims to create a detailed model of every single building in Great Britain.

All these projects are designed to arm planners and policy makers with the most accurate data possible, to help them make the best decisions they can in our collective journey to net zero.

“There are going to be issues. It’s a wicked problem we’re facing. There are so many factors at play, and the model can only do so much – but hopefully we’re making a step in the right direction.”

About the author

Steve Evans

Senior Research Fellow, UCL Energy Institute

Steve manages the team that work on the 3DStock model within the Building Stock Lab at UCL. He is currently heading up the construction of the National Buildings Database. He has recently worked on the Non-Domestic Buildings Stock model for the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ), and contributed extensively to the production of the reports.

The Bartlett in London: celebrating 200 years of UCL

This story is part of the Bartlett in London series from the UCL Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment.

In celebration of UCL's bicentenary in 2026, this series of stories explores our impact on the built environment of London – from creating healthier and more sustainable living, to supporting local communities and documenting London’s rich history.

Produced with support from the UCL Innovation and Enterprise Faculties Innovation Fund.

Learn more about the global energy transition

The UCL Energy Institute offers world-leading undergraduate, Master's and PhD degrees that prepare our students for careers in energy demand, and energy economics and policy.

Story produced by All Things Words

© UCL The Bartlett 2024