Can London’s drivers go electric?

London’s electric vehicle charging network needs to expand rapidly to hit the UK’s 2035 zero emissions target – and the rollout should be fairer

Fossil-fuel powered road vehicles are one of the largest single sources of greenhouse gas emissions, with domestic transport contributing 29.1% of the UK’s total emissions in 2023.

Electric vehicles (EVs) offer a cleaner, safer alternative. In built-up places like London, reducing transport emissions also creates additional health benefits through reduced air pollution. The UK government has a set a target for all new cars and vans to be zero-emissions by 2035.

However, developing the infrastructure needed to allow more Londoners to use EVs is no easy task. The government has implemented different schemes to accelerate adoption of EVs on the supply-side and demand-side, such as grant schemes and other mechanisms.

But despite these measures, the rollout faces additional complications for Londoners starting to use EVs in the city.

There are lots of variables that EV users have to account for. The different types of charging connector, the usage cost charged by different operators, and how regularly charging stations are unavailable due to malfunction and poor maintenance.

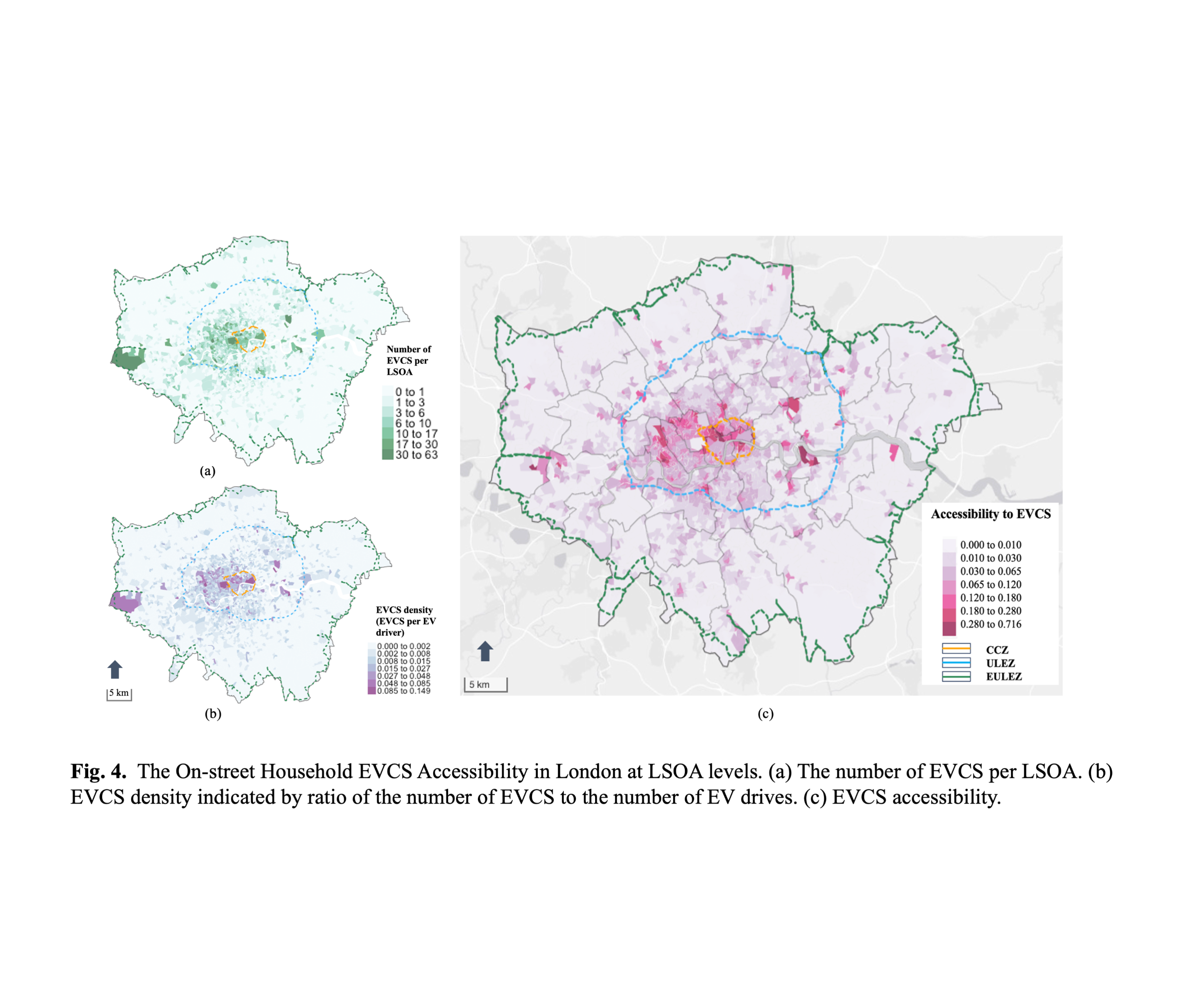

The greatest issue faced by EV users (and consequently, the biggest barrier to adoption) is accessibility – the difficulty in finding a functional public charging station near your home or place of work, that you can rely on to be available at the time of day you need it.

Photo by Andrew Roberts on Unsplash

Photo by Andrew Roberts on Unsplash

Finding fairer ways to measure charger accessibility

“Firstly, to help us identify underserved areas, and secondly, to embed the transport equity perspective. If we don’t include that perspective, we run the risk of introducing or exacerbating social issues like poverty or social exclusion.”

Dr Yuerong Zhang from the Bartlett School of Environment, Energy & Resources is the lead author of ‘Evaluating the accessibility of on-street household electric vehicle charging stations in London: Policy insights from equity analysis across emission zones’.

It’s the first major study of public EVCS accessibility in London. It’s also the first study of its kind that analyses EVCS accessibility in detail for different vulnerable groups. This more forensic approach provides policymakers with opportunities for more targeted, tailored interventions to address inequities in EVCS accessibility.

Picking apart the complexities and inequities of the EV revolution

“It’s a very dynamic situation. There are some extremely complex interactions between demand and supply, and also between different stakeholders.”

Yuerong outlines some of the complexities explored in the paper, and the reasons why London’s transport policies (in particular, the low emissions zones) have made the city an ideal candidate for this study.

“Uneven distribution contributes to a sort of ‘chicken and egg’ problem, whereby people living in an area with fewer EV chargers are even less likely to switch to an electric vehicle, further decreasing demand.”

Dr Yuerong Zhang from the Bartlett School of Environment, Energy & Resources

“Policies like the Ultra Low Emissions Zones (ULEZ) have long-term impacts on charger accessibility. They encourage people to switch to EVs, which creates a stronger demand, and could ultimately lead to more chargers in centralised areas.

“However, if not carefully planned, this additional demand can also create charging inequalities, as the private operators choose to invest their resources in these high-demand areas.

“This can create further divides, and disincentivise charging station installation in rural areas, low-use or high installation cost areas. This uneven distribution then contributes to a sort of ‘chicken and egg’ problem, whereby people living in an area with fewer EV chargers are even less likely to switch to an electric vehicle, further decreasing demand.”

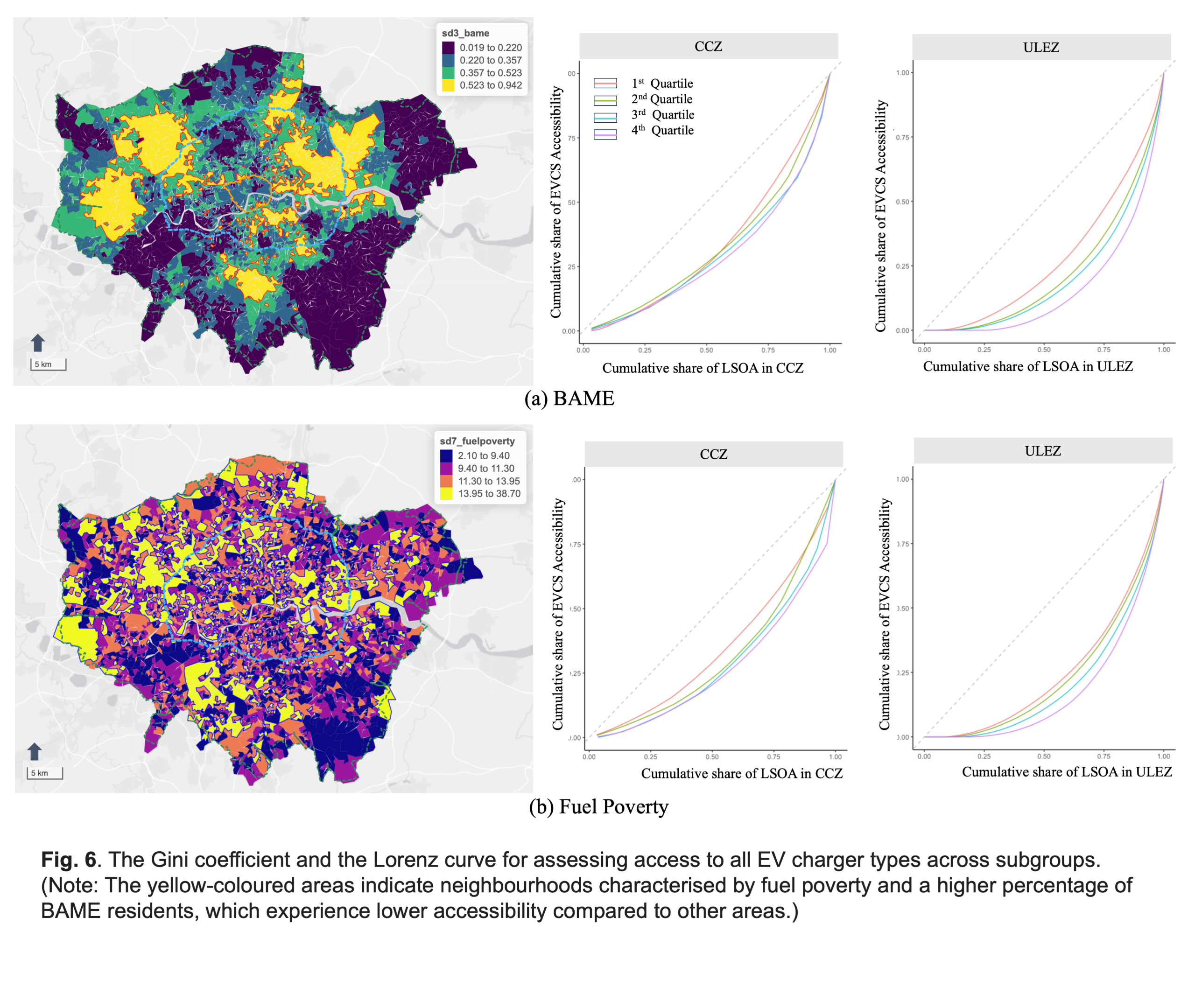

One of the paper’s key findings was the need for a more nuanced approach to identifying underserved areas and communities – and not just simply targeting funding at low-income neighbourhoods.

“The research showed us that actually, as a group, low-income people have relatively equal access to EV charger accessibility.”

When the researchers used transport equity analysis in combination with machine learning to analyse the spatial distribution of EVCS, they realised that low levels of accessibility were more closely correlated to specific factors such as fuel poverty, or greater numbers of BAME people.

These findings provide better evidence to allow local authorities to more accurately target limited resources where they’re most needed.

“One of the paper’s key findings... was that actually, low-income people have relatively equal access to EV charger accessibility.”

Dr Yuerong Zhang from the Bartlett School of Environment, Energy & Resources

Mechanisms for a fairer rollout

The UK government has already implemented several policies at both the national and local levels, with some success. Interventions such as the National Planning Policy Framework (which requires new developments to include EVCS) and grants to subsidise installations in suburban or rural areas, or to supply flats and apartments, have undoubtedly been useful.

In light of the research findings, Yuerong sees several further opportunities to ensure that the EV rollout can happen quickly and fairly.

Some of these proposed solutions are technical – for example, mobile charging vehicles, which can travel around providing charging services, have already been trialled. Other solutions include new business models, such as Co Charger, an Airbnb-style model where homeowners with private charging facilities can rent out the use of their charger.

Steering towards transport equity

Yuerong and her colleagues are currently reviewing their next steps. Future studies are likely to include accessibility analyses across other European cities, along with explorations of regional disparities between urban and rural settings.

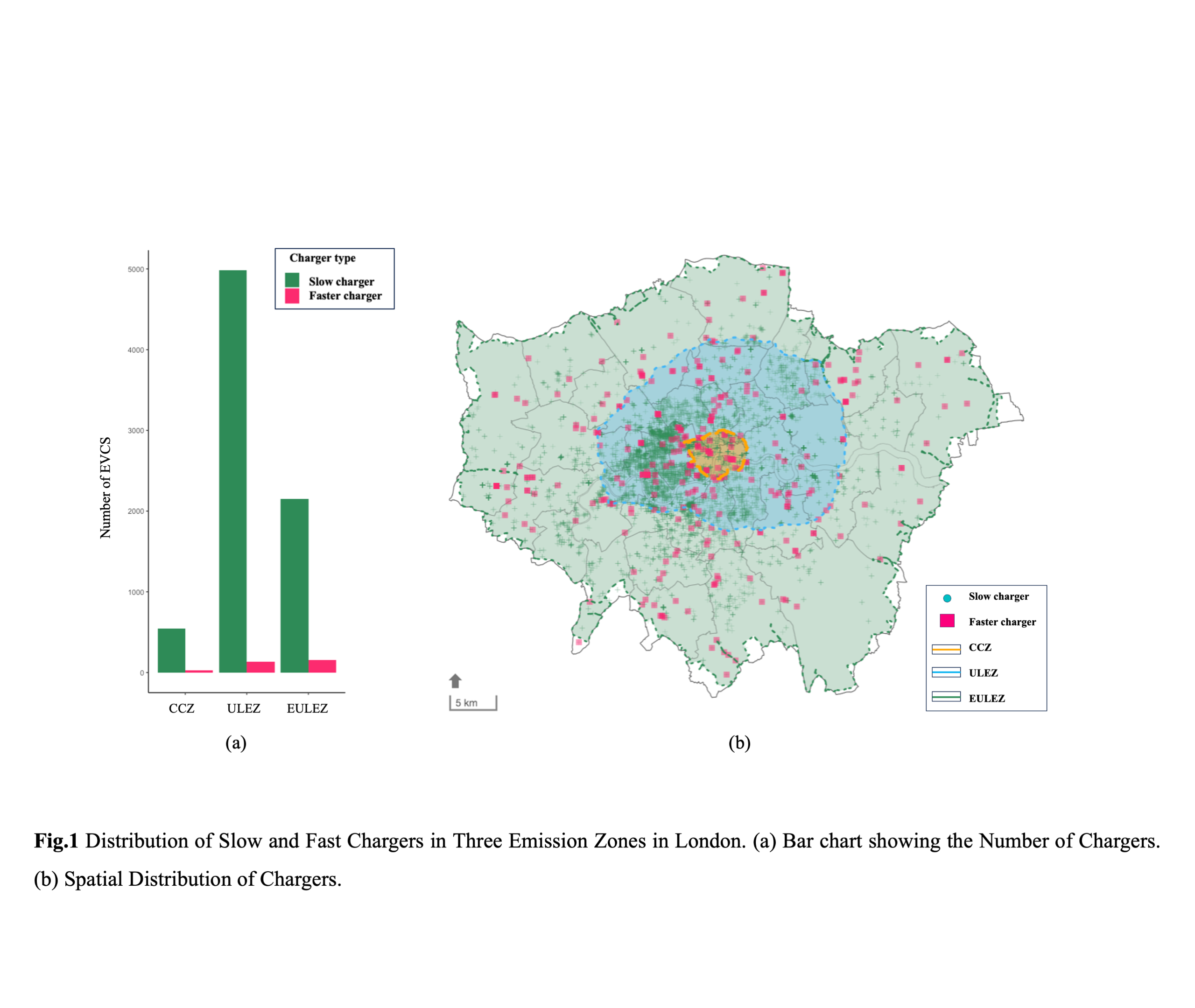

She’s also keen to add a temporal perspective to the methodologies they’ve already developed. “Charging speed (and the distribution of fast vs slow chargers) is also a huge influence on EVCS accessibility.

“Most of London’s chargers are slow chargers, which take a long time. That has a big influence on the charging experience – especially around peak times, when most people are hoping to charge their EVs.

“London is undoubtedly leading the EV rollout – not just in the UK, but among European cities. But it’s crucial that we embed the transport equity perspective. By doing so, we can work towards a decarbonised transport system that is not only efficient and forward-looking, but also inclusive and affordable for all.”

About the author

Dr Yuerong Zhang

Lecturer in Geospatial Machine Learning, UCL Energy Institute

Before joining the UCL Energy Institute, Yuerong was a Leverhulme Early Career Researcher at The Bartlett School of Planning and a Transport Modelling and Policy Researcher at UCL's MaaSLab. She completed her PhD at The Bartlett School of Planning and The Bartlett Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis.

The Bartlett in London: celebrating 200 years of UCL

This story is part of the Bartlett in London series from the UCL Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment.

In celebration of UCL's bicentenary in 2026, this series of stories explores our impact on the built environment of London – from creating healthier and more sustainable living, to supporting local communities and documenting London’s rich history.

Produced with support from the UCL Innovation and Enterprise Faculties Innovation Fund.

Learn more about the global energy transition

The UCL Energy Institute offers world-leading undergraduate, Master's and PhD degrees that prepare our students for careers in energy demand, and energy economics and policy.

Story produced by All Things Words

© UCL The Bartlett 2024